Category: Map of the Month

June Map of the Month

By Elizabeth Willis

Map: Southeast Energy Efficiency Alliance (SEEA), Source: U.S. Census Bureau, U.S Department of Energy

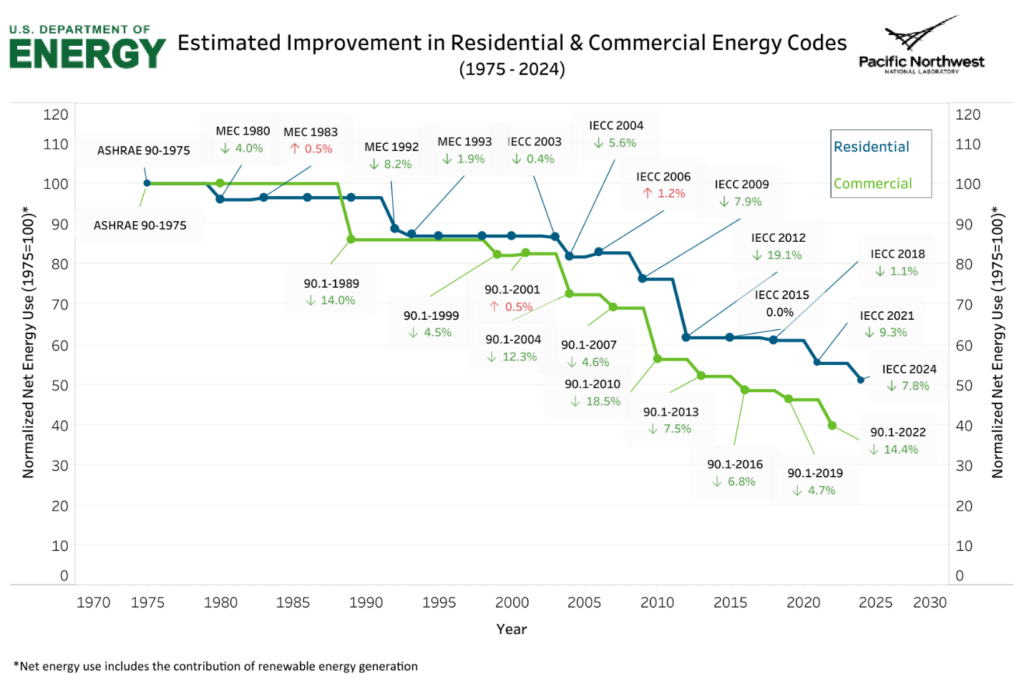

Residential construction in the Southeastern United States has ebbed and flowed over the past three decades, shaped by economic cycles, population shifts, and policy changes. Among these influences, statewide updates to building energy codes have attracted growing attention. Do they meaningfully affect construction activity? Or are their effects overstated?

This month’s map looks at the relationship between residential building activity and the implementation of statewide energy codes across the region. As the Southeast continues to experience high rates of population growth and demand for affordable, resilient housing, policymakers and industry professionals should consider how residential energy efficiency measures can be advanced without constraining development.

Using information from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Building Permits Survey (BPS), this month’s map displays the annual number of new, privately-owned, single-family residential building permits issued in each Southeastern state from 1995 through 2024. Overlaid on this time series are blue-flashing indicators marking the years when each state adopted a new or updated version of its residential building code. By visualizing these two datasets together, the map offers a regional snapshot of how construction activity has evolved over time—and whether building code updates influence permit volumes.

The Building Permit Survey (BPS) data used here is publicly available through the U.S. Census Bureau and represents an estimate of new residential building permits. It does not include information on renovations, remodeling, or additions. The intent of this visual is to observe large-scale trends in Southeastern states and contextualize them within the timeline of code adoption.

Most Southeastern states have updated their building energy codes at least once – often multiple times – since 1995. Yet in nearly all cases, these updates do not correspond with sharp declines in new residential construction. In fact, building permit volumes often continue to rise even after major code adoptions. The one clear and dramatic exception is the 2008 housing market crash, which triggered a steep regional decline in permit numbers. However, that downturn was rooted in macroeconomic instability, not regulatory change or code updates.

State-by-state patterns provide further texture. Florida, for instance, consistently shows the highest permit volumes in the region, driven in part by sustained population growth. North Carolina stands out for its triennial code update cycle, which has not hindered its steady stream of residential development. Even in states that have adopted relatively stringent codes – such as Georgia or Virginia – there is no evidence to suggest a long-term construction suppression following code implementation.

The data suggests that these impacts do not translate into a slowdown of regional construction. Instead, residential construction activity remains largely robust, even through multiple rounds of code revision. The dominant influences on residential construction activity are market-driven: availability of financing, consumer demand, labor supply, and broader economic health.

Ultimately, statewide energy code updates, though sometimes perceived as a potential hindrance to development, have not restrained residential construction in practice. Policymakers and industry professionals should consider this perspective when evaluating future code proposals and updates. While regulation warrants scrutiny, the data in this map suggests that energy codes have largely coexisted with a robust, responsive housing market in the Southeastern United States. Alongside sustained patterns of residential growth, building energy codes are a key tool for advancing public health, safety, and affordability. By establishing minimum standards for ventilation, insulation, and mechanical systems, these codes improve indoor air quality, reduce risk of respiratory illness, increase comfort, and lower energy burdens. Over the lifespan of a home, they also yield significant cost savings for residents by improving efficiency and reducing utility bills (NEEP, 2021).

SEEA has previously published The Economic Impact of Commercial Energy Codes in the Southeast, which found that stronger codes do not significantly hinder commercial construction. You can access the full report here.

March Map of the Month

By Laura Diaz-Villaquiran

Source: Federal Insurance Office, U.S. Department of Treasury.

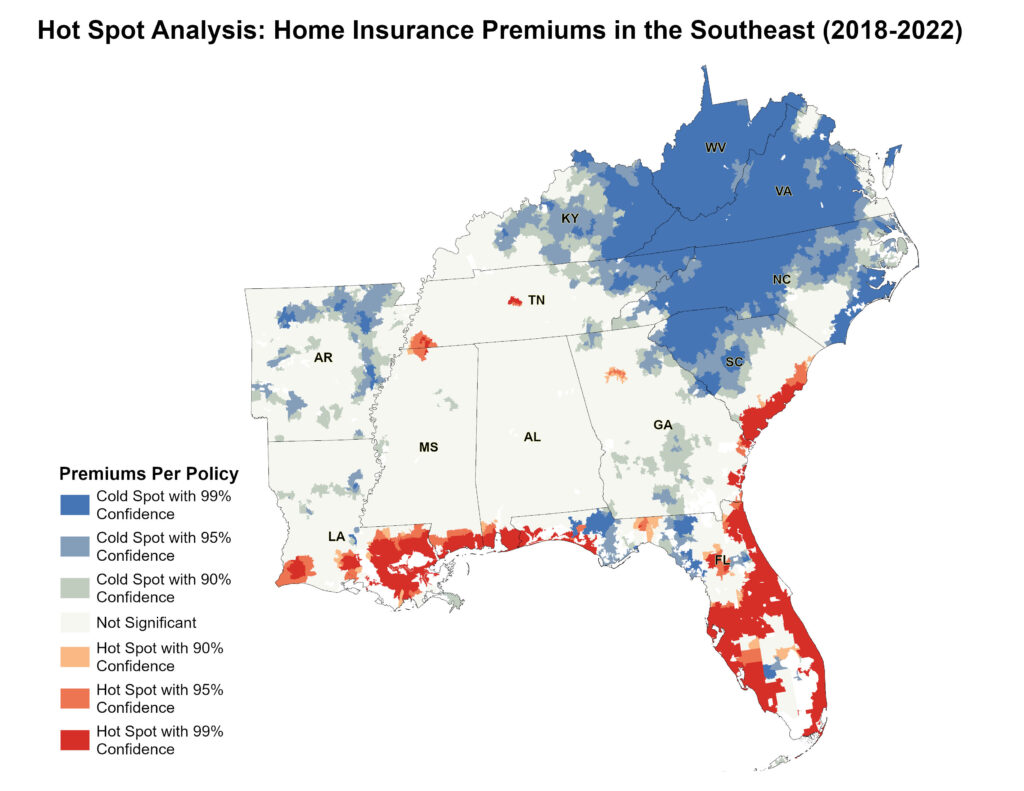

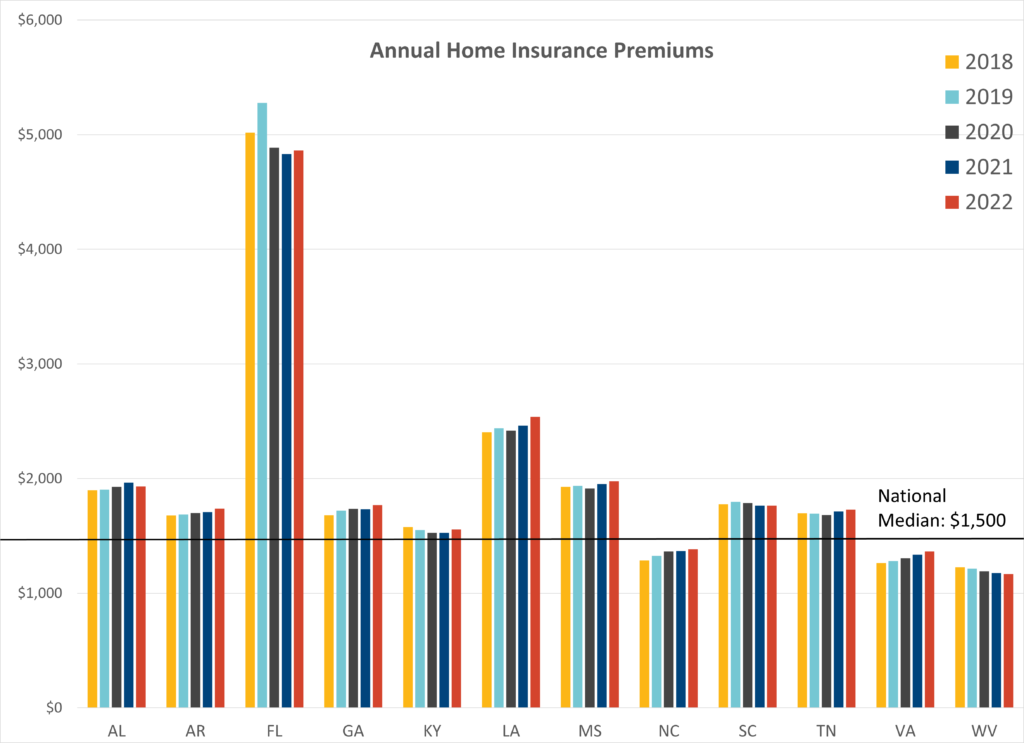

Home insurance costs are rising across the Southeast, threatening housing affordability for homeowners and renters alike. With the frequency and severity of climate-related disasters increasing, insurers are passing higher costs onto policyholders. Between 2018 and 2022, home insurance premiums written by the top 10 insurers in the region surged from $9.4 billion to $14.3 billion. Florida and Louisiana have been hit particularly hard and have some of the highest premium increases and non-renewal rates in the country.

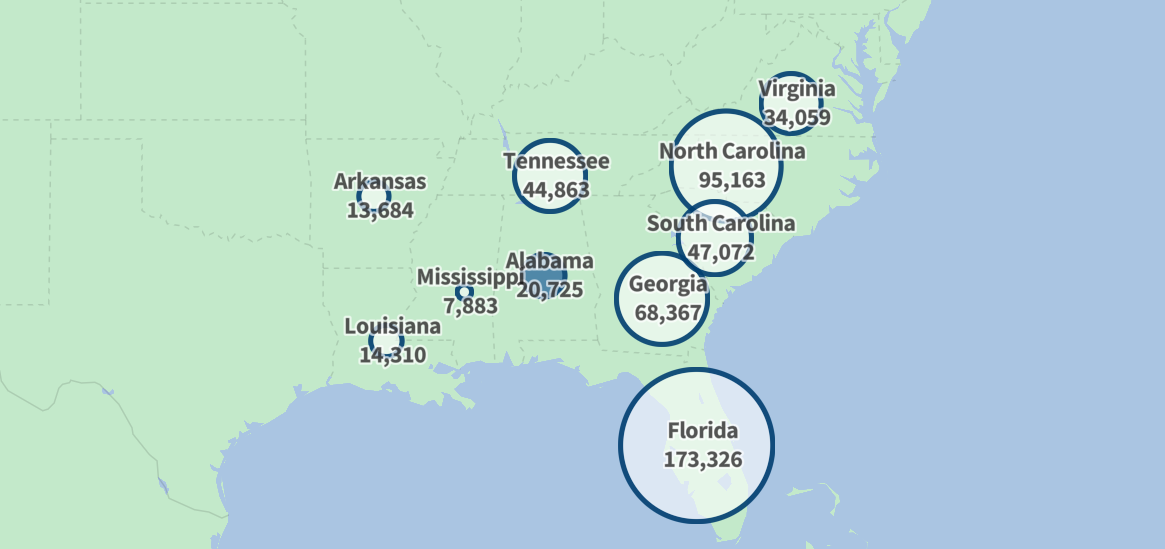

Using data from the same period provided by the U.S. Department of the Treasury, this month’s map highlights spatial patterns of home insurance costs across the Southeast through a geographic hot spot analysis. This dataset consists of comprehensive home insurance policies, which make up 85% of the home insurance market in the U.S. A hot spot analysis is a geospatial method used to detect statistically significant clusters of high or low values compared to surrounding regions. Insurance rates are calculated based on location, home value, and risk exposure. Nationally the median cost of home insurance was $1,500, while the average premium for that same period was $1,900. For the Southeast, the median premium was $1,600. See the recent average annual home insurance premiums for Southeastern states below:

This month’s map highlights areas where insurance premiums are high and cluster with other high values, with 99% confidence. Hot spots are concentrated along the Gulf and Atlantic coasts, while areas with lower premiums, also with 99% confidence, are primarily found further inland and north, in states like Kentucky, Virginia, West Virginia, and western North Carolina. In climate-vulnerable states like Florida, where extreme weather events have led to frequent insurance payouts, insurers have hiked premiums to remain solvent.

Beyond rising premiums, home insurance availability is shrinking as insurers withdraw from high-risk areas. Between 2018 and 2022, the average non-renewal rate in the Southeast (1.43%) was 38% higher than the national average (1.04%). This trend accelerated in 2023, with North Carolina and South Carolina experiencing sharp increases in non-renewals. Florida had the highest share of non-renewals, with insurers citing hurricane-related losses as the primary reason for exiting the market.

For homeowners, insurance is a necessity. Lenders require coverage to secure mortgages, and without it, banks can foreclose on homes. For renters, rising insurance costs can translate to higher rents, as landlords pass increased premiums onto tenants.

A 2025 First Street report found that in many Southeastern cities, insurance costs are outpacing home price growth. Traditionally, the region offered lower housing costs, but the risk of extreme weather has pushed insurance from 8% of mortgage payments in 2013 to more than 20% by 2022. Homeowners in Miami (322%), Jacksonville (226%), Tampa (213%), and New Orleans (196%) have seen the steepest premium increases in the region.

As the Southeast braces for the impact of rising sea levels, extreme heat, and increasing hurricane activity, planning for resilience is more critical than ever. Mitigation strategies will play an essential role in ensuring long-term housing is affordable and resilient. Improving residential energy efficiency can play a role in enhancing the resilience of housing during extreme weather and improving housing affordability to offset premium increases. Strengthening building codes, expanding access to energy efficiency, and investing in resilient infrastructure will be key in offsetting rising insurance costs and protecting homeowners and renters across the region.

February Map of the Month

By Amy Lovell

Map: Southeast Energy Efficiency Alliance (SEEA) Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)

After decades of steady demand, power consumption is increasing at unprecedented rates across the United States. According to one recent study, there will be 128 GW of new power demand – around 30% of the 2024 electric capacity – added to the grid just in the next five years, largely fueled by the outsized energy needs of data center and computing facilities. A 2024 report from McKinsey lists Georgia and Florida as “emerging demand,” in addition to lower but fast-growing demand in five other Southeastern States where companies have been rapidly siting new computing and manufacturing facilities.

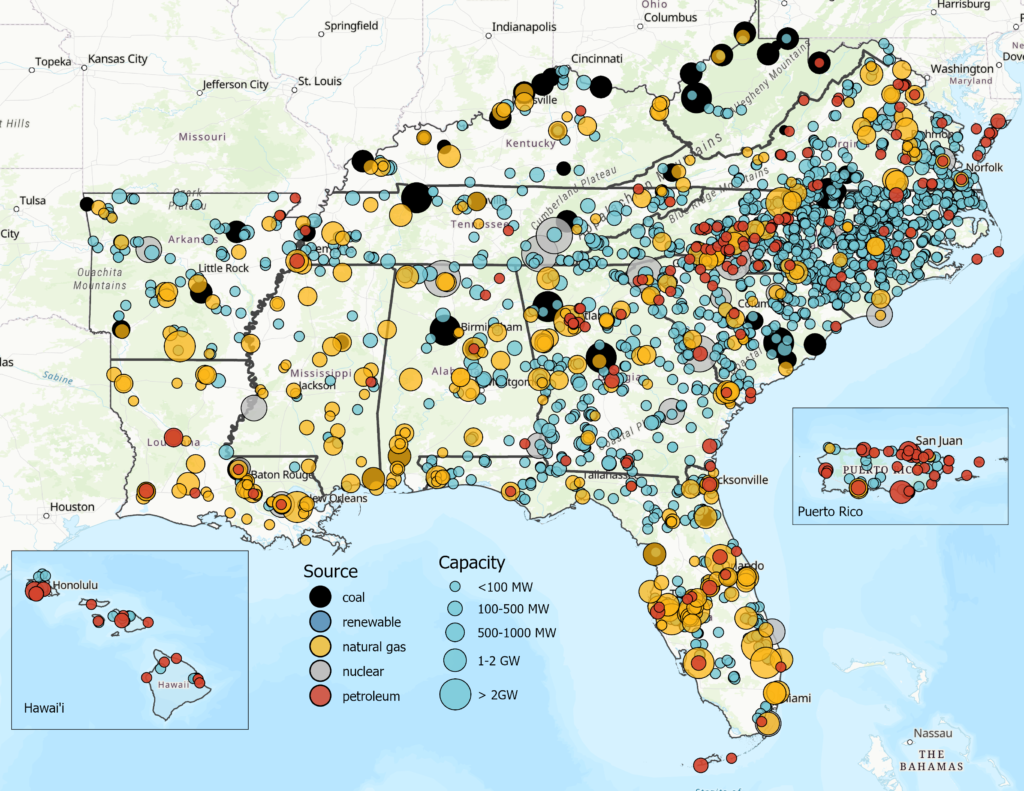

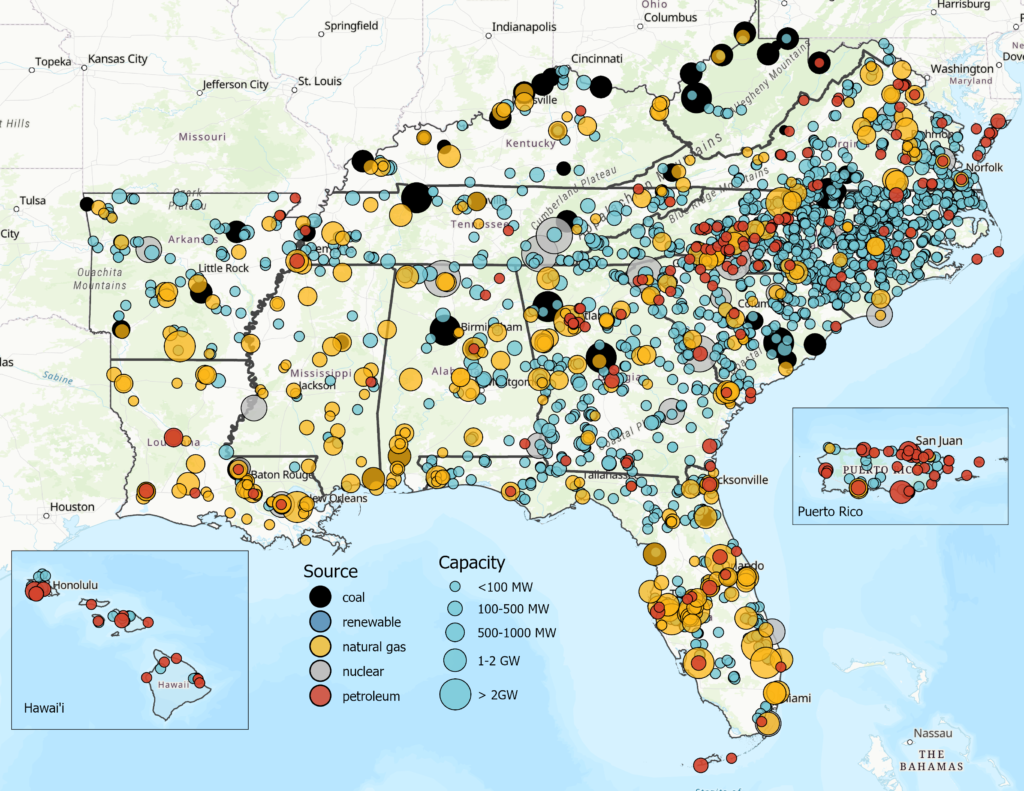

This month’s map considers the implications of this unprecedented load growth in the South. We use data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) to review how Southern utilities currently generate power, as well as the expected energy and financial implications of new generation infrastructure that will be required to meet these needs.

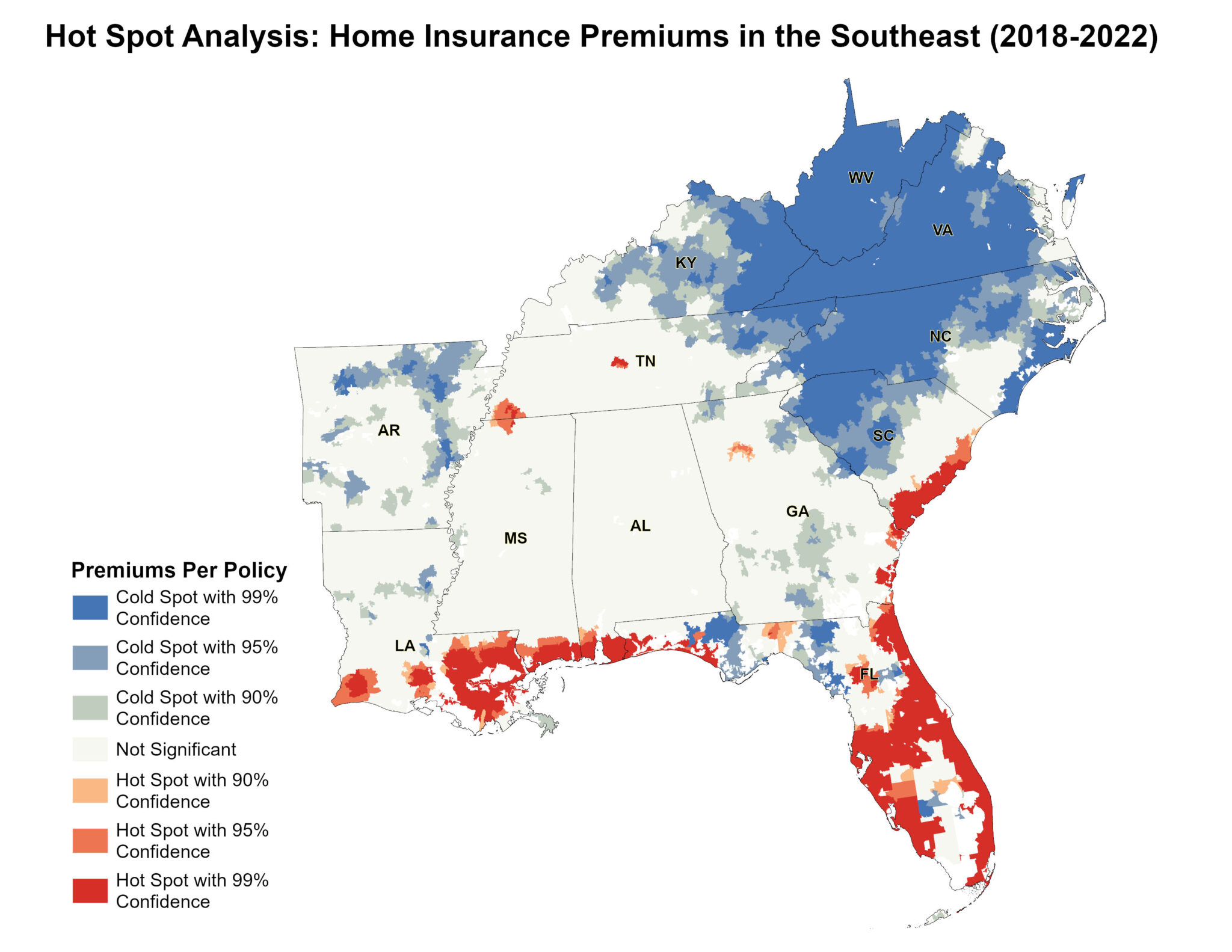

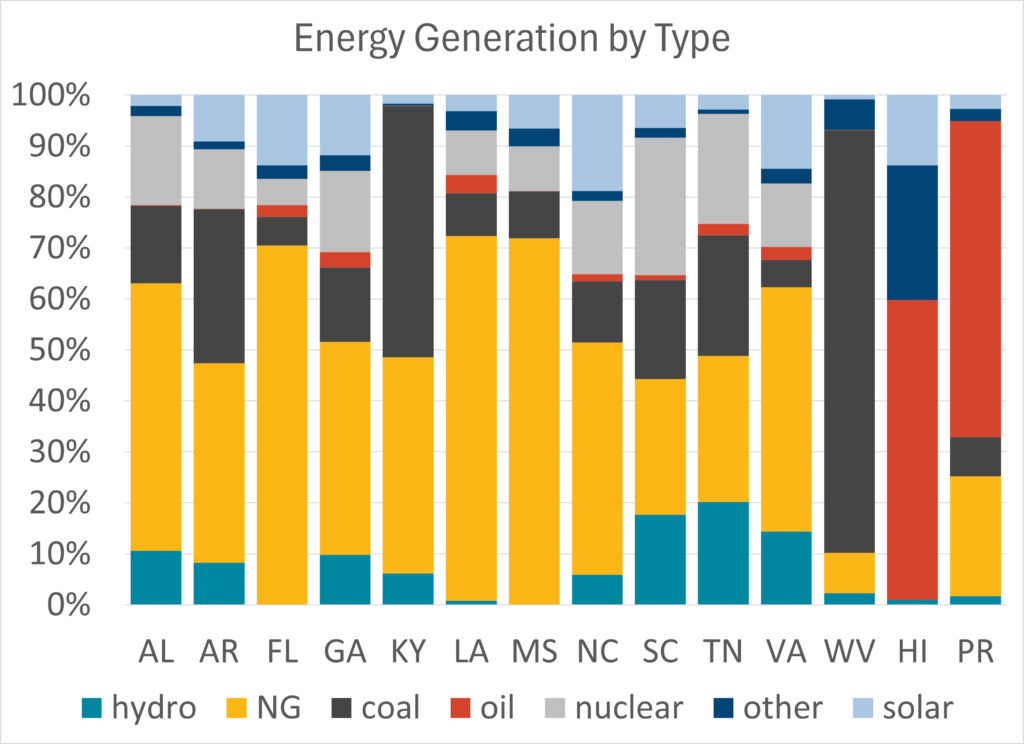

The Southeast has a power generation capacity of 370 Gigawatts (GW), which is generated by a diverse portfolio of power plant types as shown in the chart below. Natural gas is the leading fuel source. It supplies around half of the region’s electric generating capacity, and is the main fuel in Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi. Coal-fired power plants supply 16% of the region’s electricity, dominating power generation in Kentucky (68%) and West Virginia (74%). Nuclear power is a consistent energy source in all areas except the islands, Kentucky, and West Virginia, providing 11% of the region’s electricity. Nuclear power supplies more than one-third of electric power in Alabama, Georgia, and the Carolinas. Averaged over the region, oil comprises 2% of the power supply. Hydroelectric and pumped storage facilities throughout the region contribute 7%, with other renewable energy sources – including utility-scale solar – supplying the balance (11%).

Profile of the energy generation capacity by type for the Southeast region, as well as the tropical islands of Hawai’i and Puerto Rico. The region draws a large portion of its energy capacity from natural gas-fired (NG) power plants, with the other half well diversified across other fuels. The “other” category includes batteries, biofuels, geothermal, or wind, which is not a significant contribution to power generation in the region.

The U.S. islands have a different energy mix given their climatic and geographic constraints. Petroleum-fired power plants dominate the energy supplied in the islands of Hawai’i and Puerto Rico, in addition to supplying small amounts of electric power in five other states. While the islands are largely reliant on petroleum oil-fired power plants, Hawai’i has committed to fully renewable electricity generation by 2045 and Puerto Rico has committed to a fully renewable portfolio by 2050 (en español), after a study in partnership with the Department of Energy.

Between 2018 and 2024, the Southeast added 21 GW of net new capacity (6%). New utility-scale solar facilities contributed the most capacity, with 25 GW (a 340% increase from 2018), with natural gas facilities adding an additional 19 GW (11%). Wind power capacity is small compared to other regions, with 400 MW (32% increase from 2018). After the decommissioning of some coal power plants, the capacity of coal-fired generation has decreased by 25 GW (28%), almost entirely offset by the additional solar generation capacity.

Expected power increases in the Southeast may strain available generation resources. With nationwide power demand predicted to increase 2% in both 2025 and 2026, the Southeast portion of the increase will require more than 15 GW of additional capacity by the end of 2026. If this were to be generated entirely from utility-scale solar power at 2022 prices ($1,588/kW), it would cost $24 billion to construct. From entirely natural gas ($820/kW), the cost would be $12.5 billion, along with an additional $2.4 billion annually for the fuel at $18/MWh.

In this map, each dot represents a different type of power generation facility in the Southeast, Hawai’i and Puerto Rico, with its full capacity indicated by the size of the circle. Nuclear power comes from 40 high-capacity generation units across the region, renewable (hydroelectric and solar shown in blue) generation comes from 2,400 smaller-capacity facilities, and natural gas provides the dominant share of regional electricity. Utility-scale electricity generation is not evenly spread across the region: facilities must be connected to the power grid to dispense to customers, and transmission lines must expand to incorporate new capacity to meet increasing demand.

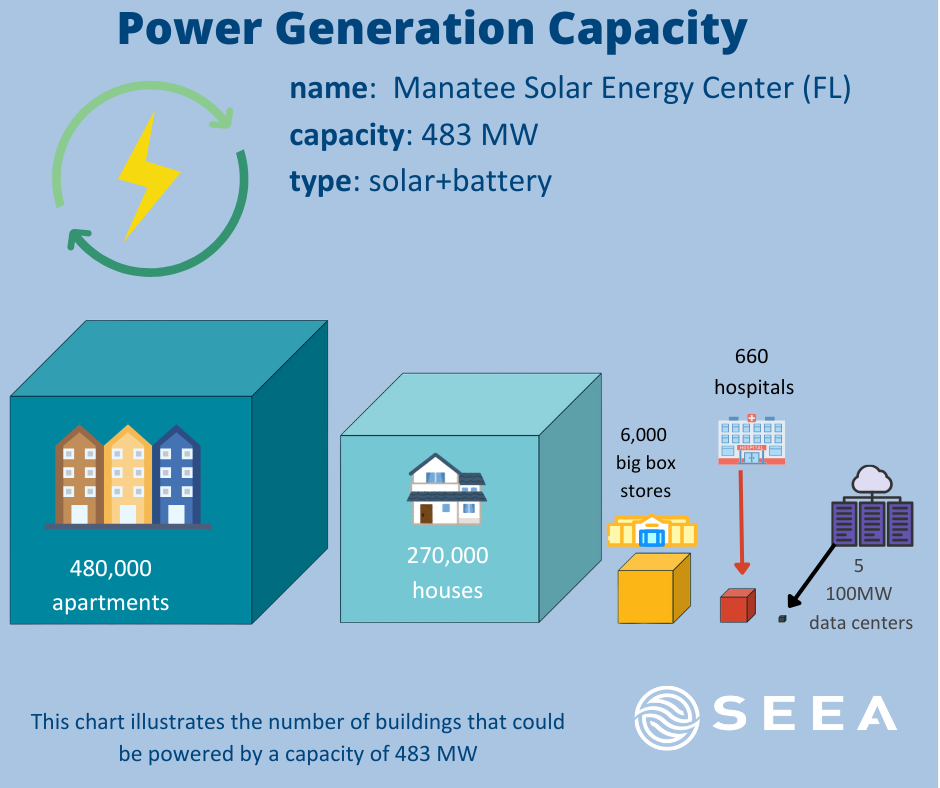

As power demand increases, we anticipate that the region will continue to rely on a diversified portfolio of sources to meet its power needs. Each new power plant built will contribute to meeting new demand: illustrated below are approximate numbers of buildings that could be powered by a single large solar facility if it were devoted entirely to a single type of building stock.

But we should not meet this need simply by building more generation facilities. Energy efficiency must be a critical component of the region’s diverse power mix. Continued efforts to expand energy efficiency in commercial, industrial, and residential sectors and added demand flexibility can reduce existing demand and work in tandem with other efforts to meet growing power demands. As the Southeast works to make sure the power supply remains reliable in the face of historic increases in power consumption, energy efficiency must be a critical tool to save energy, reduce demand, and lower costs for residential and business customers.

January Map of the Month

By William D. Bryan, Ph.D.

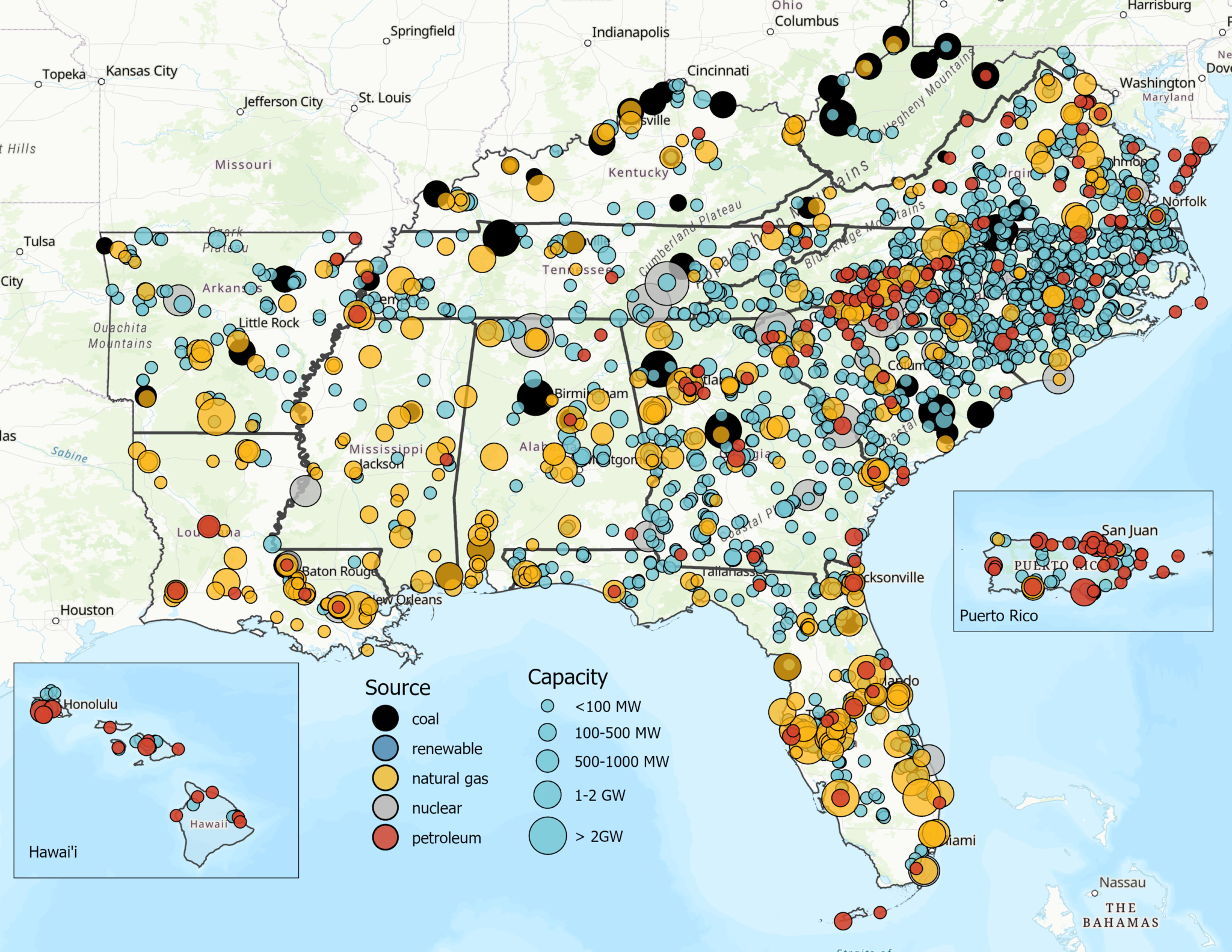

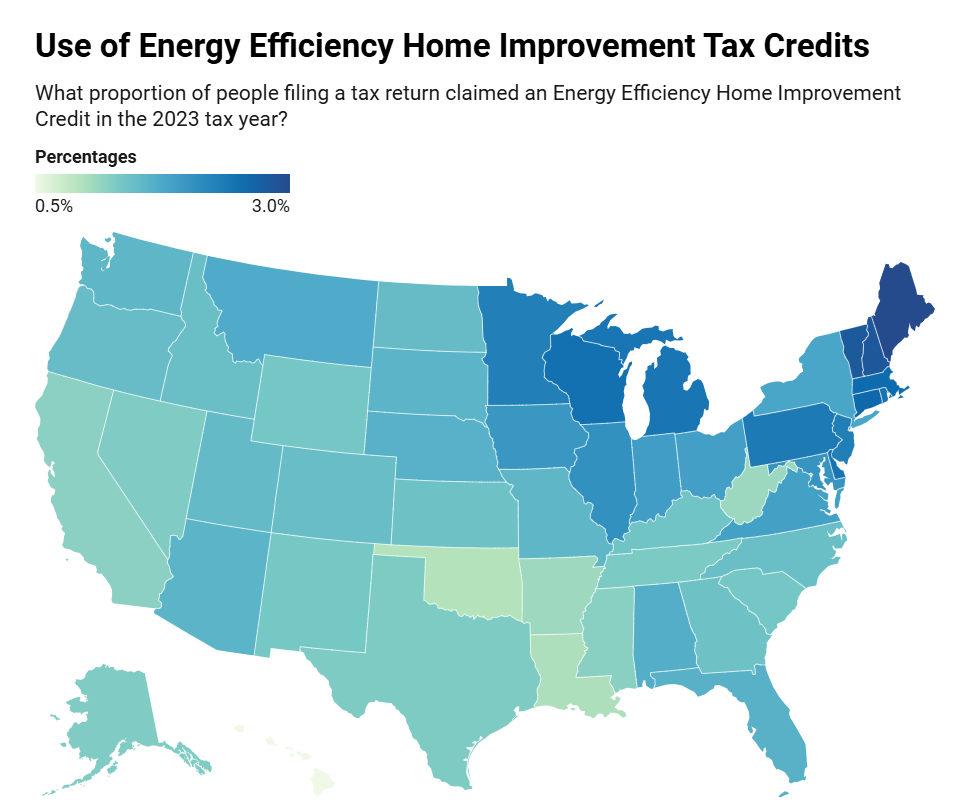

Tax season is fast approaching, and if you have invested in energy efficiency upgrades to your home over the past year you may be eligible for a federal tax credit that can offset some of your costs. The Energy Efficiency Home Improvement Credit, sometimes called the 25(c) credit, provides an annual tax credit of up to $3,200 for qualifying households that have invested in energy efficiency improvements since 2023. This includes up to $1,200 for efficient doors, windows, skylights, insulation, air sealing as well as for home energy audits. It also includes up to $2,000 per year for certain heat pumps, water heaters, or for stoves and/or boilers powered by biomass. Using data from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), this Map of the Month explores the impact of these tax credits.

Since it was expanded in 2023 with the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, the 25(c) credit has been used by millions of households across the United States. In the South, more than 500,000 residential households claimed this tax credit in 2023, putting almost half a billion dollars back into their pockets – around $904 per household, on average – to offset the costs of making their homes more efficient, more affordable, and safer. Virginia, Florida, and North Carolina had the highest proportion of filers who took advantage of the 25(c) credit, with more than 150,000 households in Florida alone using it to offset home improvement costs.

Nationally, the most popular uses of the 25(c) credit were to support the costs of air sealing and upgrading insulation, followed by replacing exterior windows and skylights, upgrading central air conditioners, and replacing exterior doors. More than 250,000 households across the nation used this credit to offset the costs of installing an electric or natural gas heat pump water heater, with 100,000 claiming the credit for installing highly efficient heat pump water heaters.

Although people of all incomes have benefitted from these tax credits, they tend to be used most by households with higher incomes. The majority of claims nationally (38%) were made by filers who made between $100,000 and $200,000 in 2023. Households making under $100,000 made up less than half of the total filers claiming a 25(c) credit (42%).

The 25(c) tax credit is a critical source of support to help households offset the costs of upgrading the quality of their homes, improving the long-term affordability of their housing. But Southern households lag the rest of the nation in claiming this credit and are leaving money on the table. In 2023, just 1.5% of households in the South reaped the benefits of 25(c), compared to 2.5% nationally. Louisiana, Arkansas, and West Virginia had some of the lowest rates of participation in the entire nation.

Housing costs are at historic highs, and millions of households in the South could benefit from home renovations that improve comfort and affordability. The 25(c) credit provides a key mechanism to support these upgrades in the region’s existing housing as well as spurring business for the tradespeople that provide home renovation services. So, be sure to file for a 25(c) tax credit if you have qualifying upgrades that improve your home’s comfort and value, if you want to keep more money in your pocket.

December Map of the Month

By Laura Diaz-Villaquiran

Source: U.S. Census Bureau - American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian Areas (AIANNHAs). U.S. Department of Energy – Low-Income Energy Affordability Data Tool (LEAD).

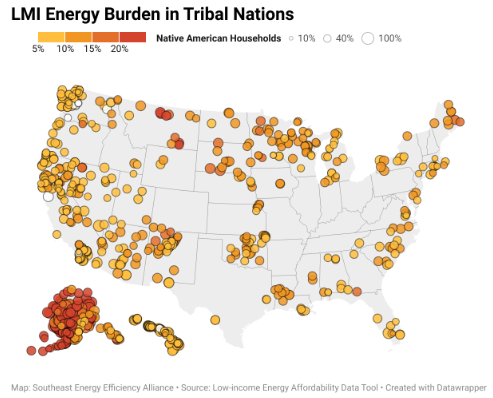

Native American communities in the United States face steep barriers to accessing energy efficiency and clean energy resources, while experiencing disparities in access and reliability of electric service. According to a 2023 report from the U.S. Department of Energy, tribal communities experience higher than average energy costs and burdens, while also having a higher number of unelectrified homes and a greater frequency of power outages.

December’s map of the month uses data from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Low-Income Energy Affordability Data (LEAD) tool to highlight the energy burdens faced by low- and moderate income (LMI) American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian households. The geographies in this map come from the U.S. Census Bureau and include federally recognized tribal lands, state-recognized reservations, off-reservation trust lands, tribal subdivisions, Alaska Native Regional Corporations, and Native Hawaiian home lands.

Energy burden is a measure used to assess a household’s ability to afford their energy costs and is calculated by dividing a household’s annual energy expenses by their income. Nationally, Native American households face median energy burdens that are 45% higher than that of white (non-Hispanic) counterparts.

We find that 86% of low- and moderate-income Native American households have high energy burdens, meaning that they pay at least 6% of their income for their energy bills. Out of those households, 50% have energy burdens that are considered severe, which require spending at least 10% of income to cover energy expenses.

The highest tribal energy burdens are concentrated in Alaska. This is driven by Alaska’s high per capita energy consumption, reliance on diesel-fueled electric generators, and sub-Arctic temperatures. Many rural communities in Alaska are not connected to the Railbelt energy grid and have high-cost utilities resulting from this lack of interconnectivity and the expense of delivered fuels.

Tribal communities' experiences of energy insecurity are shaped by legacies of colonization, forced displacement, marginalization and federal policies that have contributed to the disparities that exist today.

Despite energy affordability challenges, Native communities have been at the forefront of the environmental and energy justice movements and are leading the way in shaping a clean energy future, and DOE’s 2023 report notes that federal investments are “having a tangible impact” on improving energy access and reliability.

The U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Indian Energy Policy and Programs contains a Tribal Energy Projects Database where you can learn more about 221 tribal-led energy projects across the country, with 151 of those focusing on workforce development, weatherization, photovoltaic energy generation, energy efficiency, and the deployment of renewable energy technologies.

Federally funded projects support indigenous communities' energy sovereignty and climate resilience. Solar installations, for example, help reduce the need for transported fuels to remote locations and protect the residents of tribal lands from rolling utility blackouts.

Additionally, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently deployed unprecedented funding to support clean energy and energy efficiency projects in tribal communities through the Community Change Grant initiative. In the most recent award period, 9 projects in Alaska received upwards of $180 million in funding to support equitable climate solutions. Some of those awardees are:

- The Kotzebue Tribal Wind project, which will build two tribally owned 1MG wind turbines;

- The Huslia Village Climate Solutions project, which will provide critical water and sewer infrastructure to the Koyukuk-hotana Athabascan village. The funding for this project will be directed towards weatherizing “16 homes to reduce energy costs,” build 8 new energy efficient homes, and install grid-connected rooftop solar systems in this rural community;

- The Chenega Bulk Fuel Storage System and Renewable Integration Project, which aims to decrease Chenega’s reliance on diesel fuel through the installation of solar arrays with battery storage.

November Map of the Month

By Amy Lovell

Source: United States Energy & Employment Jobs Report (USEER)

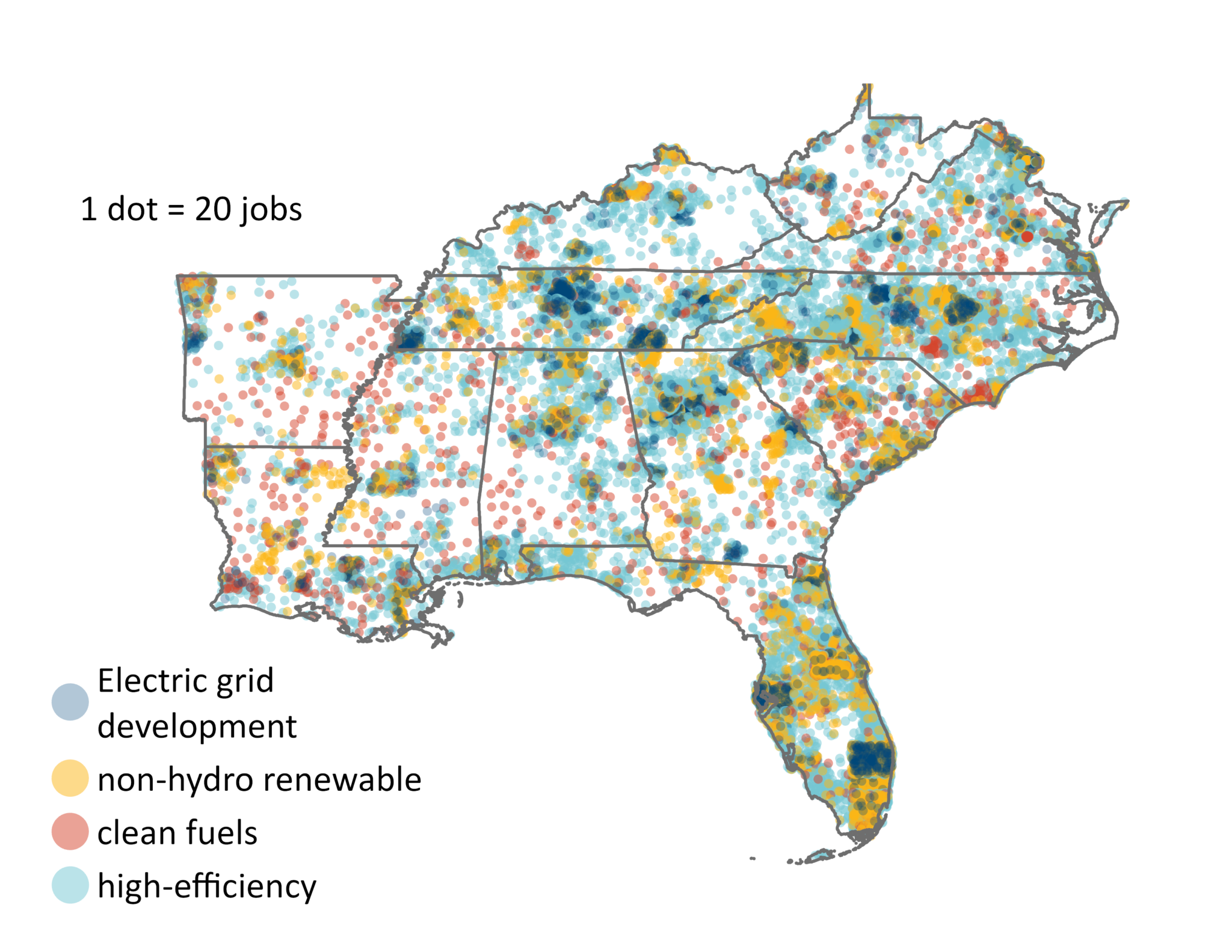

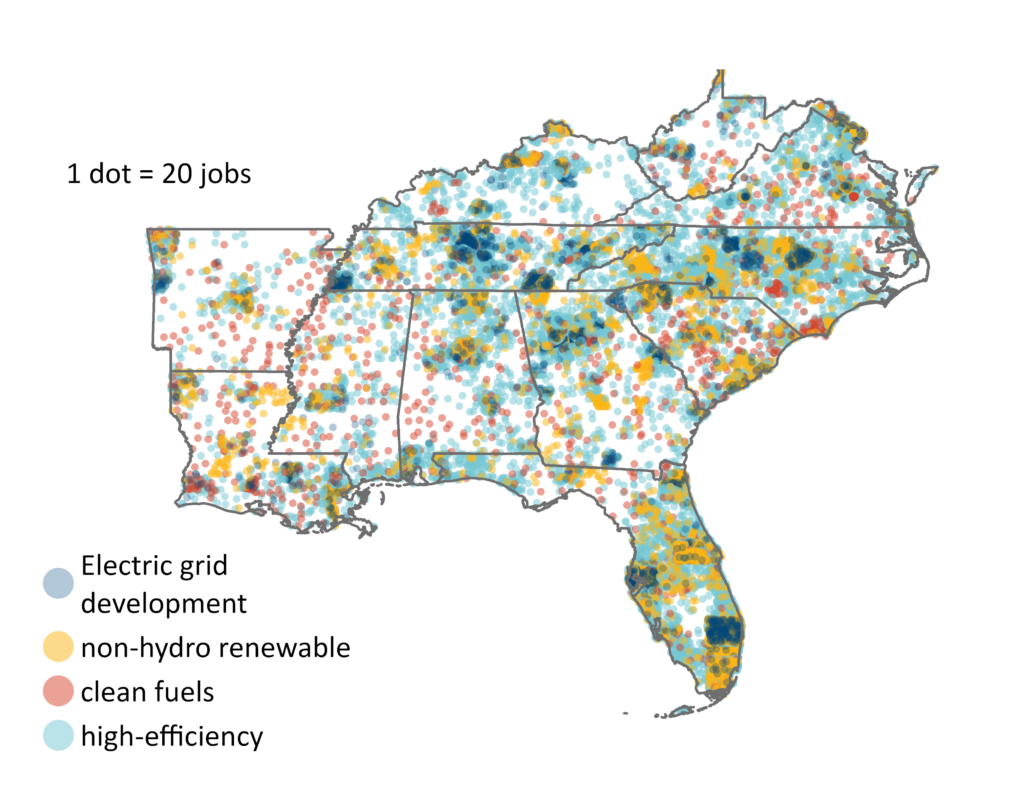

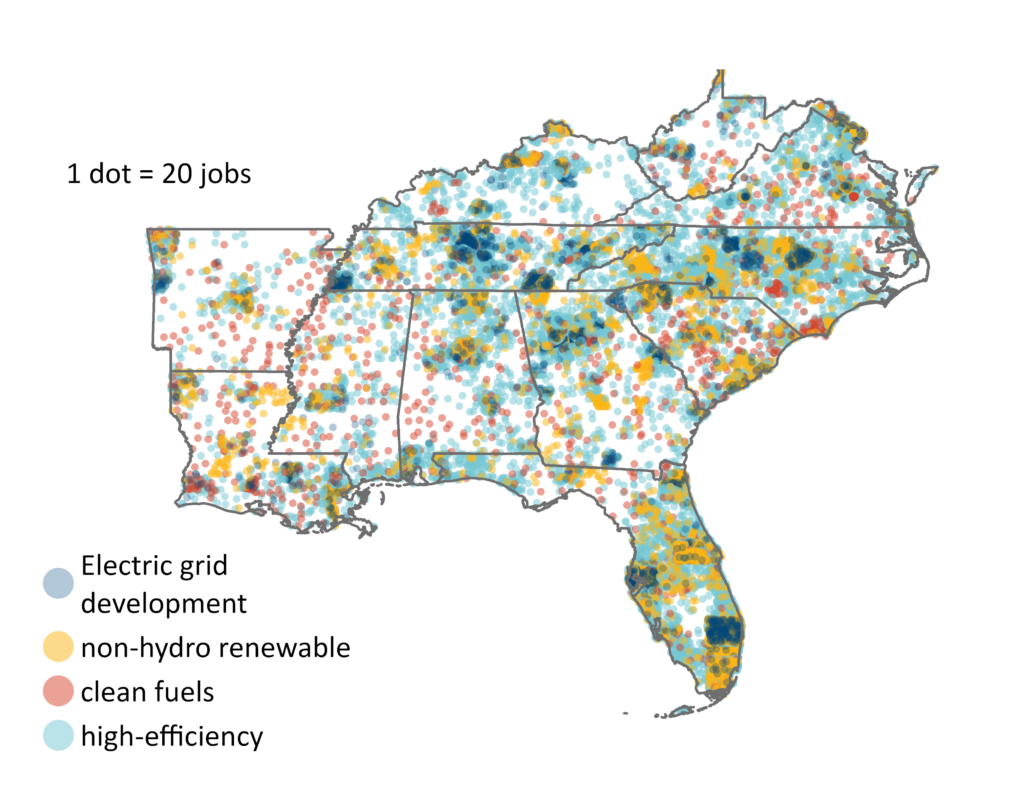

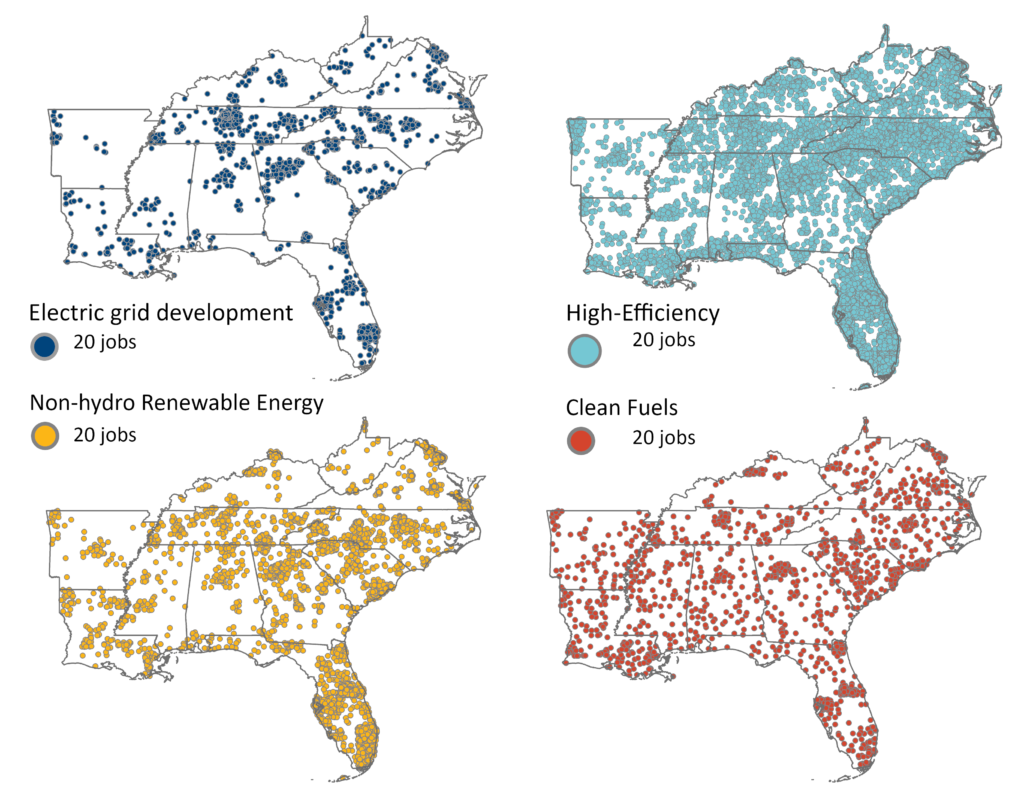

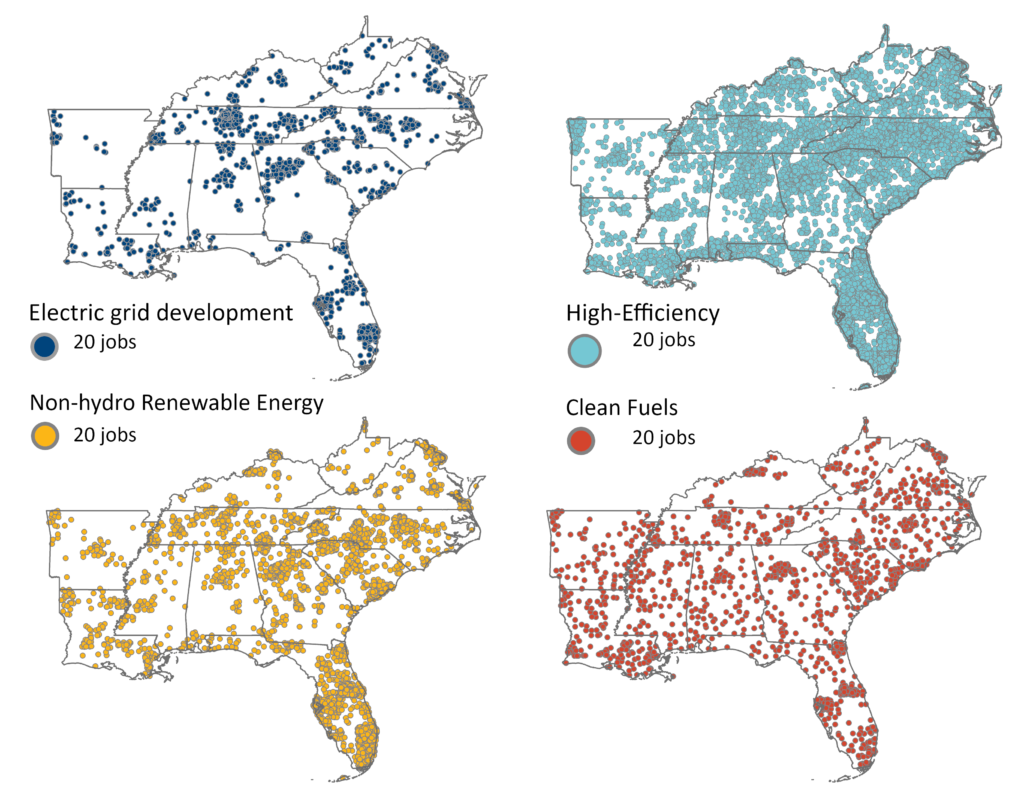

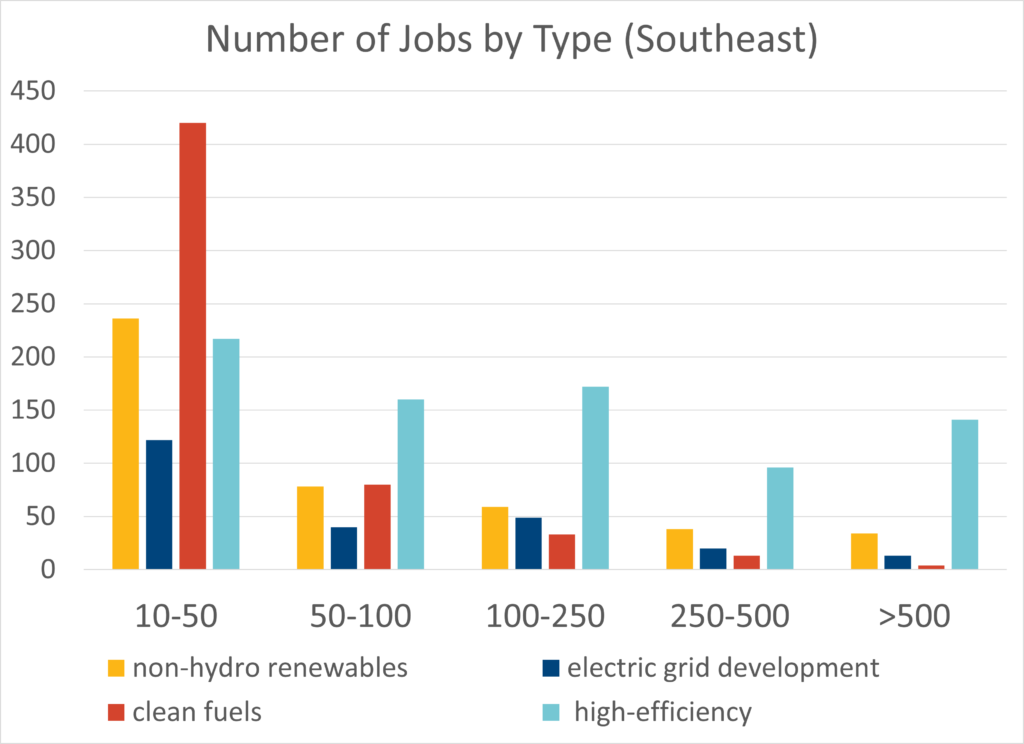

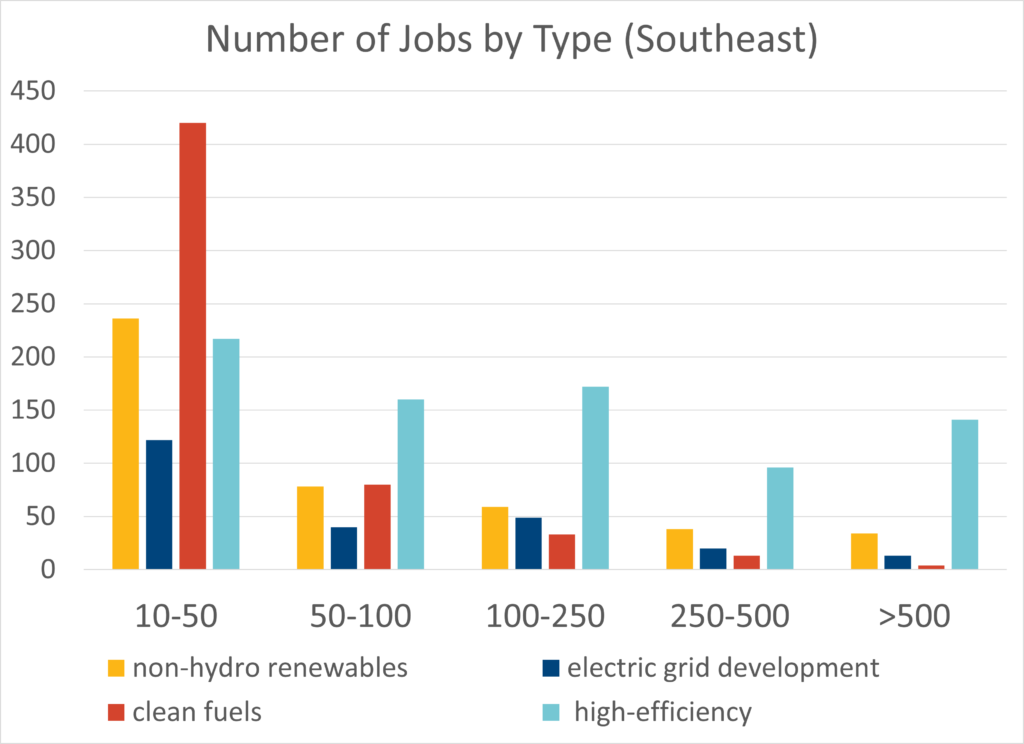

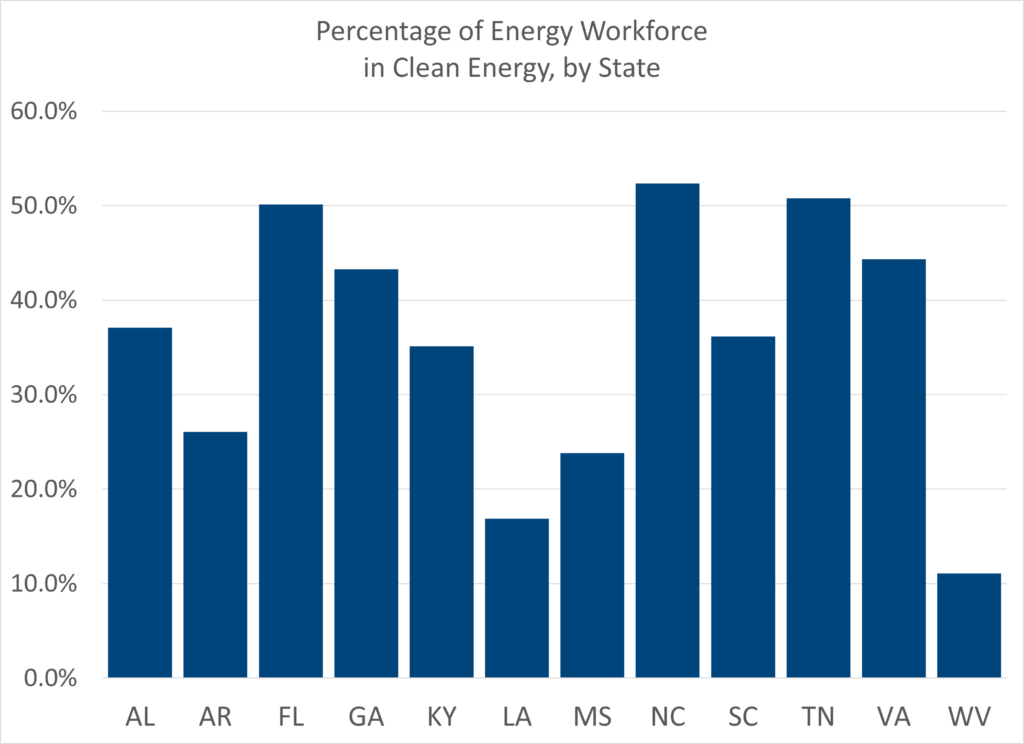

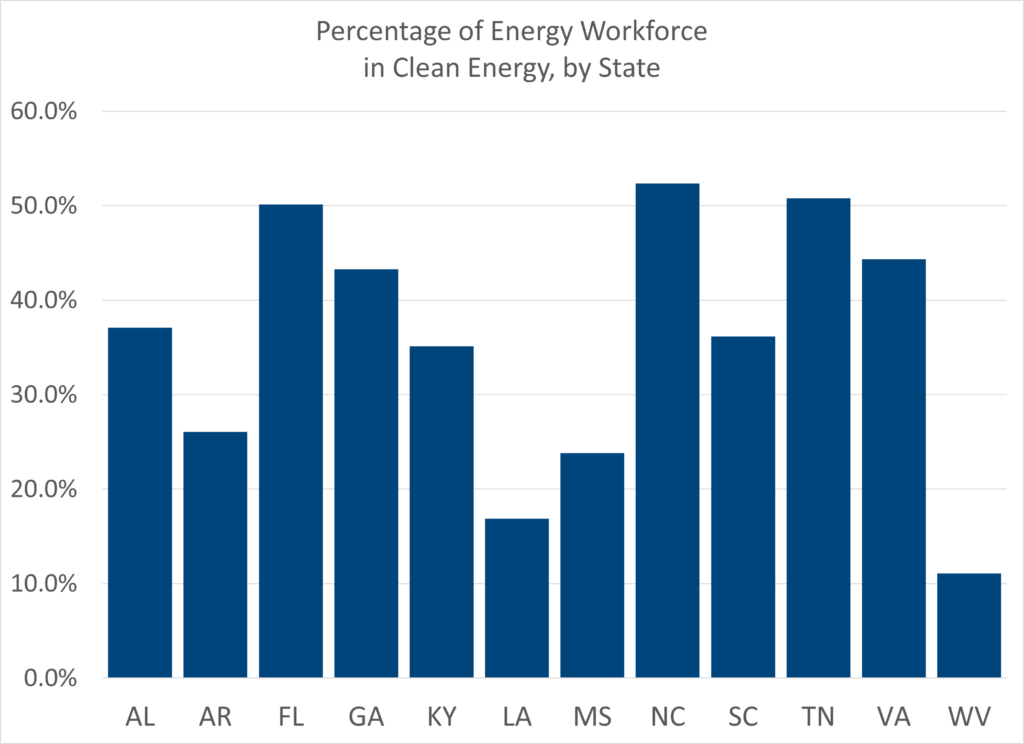

Over the past few years, a “Battery Belt” has emerged in the Southeast, where massive investments in clean energy and cleantech production are reviving the region’s manufacturing economy and creating thousands of new jobs. These jobs have rightly been at the forefront of regional and national economic development efforts and planning for the energy transition. What has been less prominent in these discussions is the region’s already-thriving clean energy workforce, which spans a myriad of job types and virtually all parts of the region.

This month’s map uses data from the United States Energy & Employment Jobs Report (USEER) from 2023 to explore the extent and impact of the clean energy workforce in the Southeast. It illustrates that clean energy is a significant source of jobs in most counties in the region, and calls attention to how diverse these jobs are across sectors and job type.

Clean energy jobs are an increasingly large portion of the energy workforce nationwide and provide 39% of the energy jobs spread across the Southeast. 87% of counties in the Southeast have a workforce of ten or more jobs in clean energy, which exceeds the national average of 83%. The region’s high-efficiency workforce is the largest and most geographically dispersed in the nation: 73% of counties have a workforce in efficient lighting, energy STAR, high-efficiency heating ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC), and advanced materials and insulation.

Of the 1.2 million non-automotive energy jobs in the Southeast, 474,613 jobs (39%) are in the clean energy workforce categories of 1) non-hydro renewable power generation, 2) electric grid modification, 3) high-efficiency or 4) clean fuels. The 340,000 high-efficiency jobs represent the largest fraction (72%) of this workforce. Nationally, 41% of energy jobs are in these clean energy categories, with 64% in high-efficiency jobs. Renewable energy employs fewer workers (40%) in the Southeast than nationwide (54%), but has been experiencing consistent growth, in part due to significant efficiency and clean energy investments in the region.

The percentages of the energy workforce in clean energy vary across Southeastern states. Florida, North Carolina, and Tennessee have over half of their energy workforce in clean energy, while Louisiana (17%) and West Virginia (11%) have the lowest fractions. Rural areas and regions with a significant Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) population have the greatest potential for job growth.

In the fuels workforce, petroleum, natural gas and coal comprise the majority (85%) of workers, with clean fuels including woody biomass and corn ethanol making up a combined 15% of the fuel workforce, comparable to the national average. Georgia (32%), North Carolina (41%), South Carolina (49%), and Tennessee (32%) have the highest portions of the fuel workforce in clean fuels.

From 2020-2023, solar and wind energy jobs grew from 35% to 40% of the power generation workforce, with North Carolina and Georgia crossing 50% of workers in renewable power generation. In the same period, the national workforce in renewables only grew from 53% to 54%, so the Southeast is realizing some potential for growth for workers in this area.

Transmission, Distribution, and Storage (TDS) jobs in the Southeast are primarily in traditional TDS, with 11% of this workforce in storage, smart grid, microgrids, and other grid modification work. Tennessee has by far the largest fraction of the TDS workforce in this category, at 26%.

While the emergence of the “Battery Belt” and transformational investments in clean energy manufacturing are key factors shaping the region’s economy growth, the Southeast has a seasoned and thriving clean energy workforce. Though jobs in renewable energy and clean fuels may be more easily recognized as part of the clean energy workforce, it also includes many jobs improving building efficiency and innovating our electric grid. This workforce has been expanding more rapidly than in the rest of the nation, and it provides opportunities for people with a range of skillsets living in virtually any community in the region to participate in the clean energy economy.

October Map of the Month

By William D. Bryan, Ph.D.

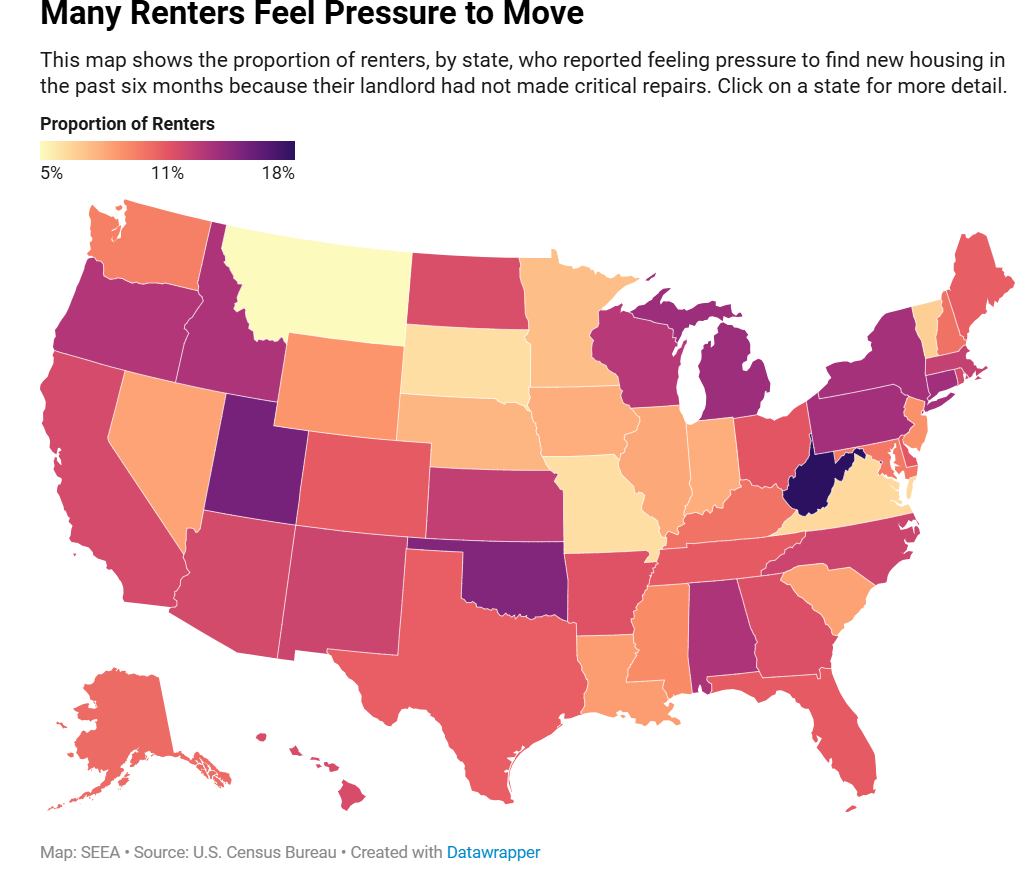

On July 1, 2024, Georgia’s Safe at Home Act went into effect. Passed earlier this year, the law establishes that for any lease signed after July 1 Georgia landlords have a “duty of habitability” and must ensure that their rental unit is “fit for human habitation.” This includes maintaining a safe and healthy property and addressing tenants’ maintenance requests in a timely manner, and it gives tenants legal recourse if these conditions are not met.

The Safe at Home Act is a critical step forward, but significant housing quality challenges remain for renters throughout Georgia and the South. A 2022 investigatory series by The Atlanta Journal Constitution underscored that thousands of renters in metro Atlanta face severe housing quality shortfalls and have little bargaining power, particularly with absentee landlords. Deferred maintenance has led to mold, pest infestations, and thermal discomfort that exacerbates health issues like asthma and can be a financial drain for tenants.

While Georgia’s new law provides a pathway to address deferred maintenance, millions of renters in the Southeast still struggle to get their landlords to make critical repairs. Deferred maintenance not only contributes to health struggles, but also undermines housing and community stability by forcing renters to search for better housing. In this way, deferred maintenance can force “involuntary moves” or displacement. While tenants may choose to leave poor housing conditions, this only underscores the lack of formal options for many tenants trying to get maintenance needs and other issues addressed.

This month’s map uses data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, administered nationally in August and September of 2024, to show the proportion of renters in each state who reported feeling pressure to move in the past six months because of unresolved repair issues with their housing.

The data make it clear that a significant number of renters face housing quality pressures that contribute to housing instability. More than half (52%) of all renters in the United States have felt pressure to move in the last six months, with 11% attributing this to a lack of critical repairs. Other factors forcing tenants to consider a move include increases in rent (19%), a missed rent payment (4%), threats of eviction from a landlord (3%), living in an unsafe neighborhood (5%), or because a landlord has changed the locks or removed tenants’ possessions from a unit (0.2%). Nationally, these issues have an outsized impact on low- and moderate-income renters as well as Hispanic renters, who are most likely to feel pressure to move due to housing conditions.

More than 9 million renters in the South report feeling pressure to move, with nearly 2 million households in the region struggling with deferred maintenance. Even in Virginia, which is generally below the national average, 41% of renters have felt pressure to move in the last six months, driven primarily by sharp increases in rents. In West Virginia, 53% of renters have felt pressure to move and nearly 18% attribute this to unresolved repairs to their housing – the highest rate in the entire nation.

Housing quality and energy efficiency are closely linked, and energy efficiency programs can provide a key source of funding to address deferred maintenance and health issues. Although the “split incentive” between renters and owners makes it difficult for renters to access energy efficiency, there are proven models that can ensure renters are able to access the benefits of energy efficiency and clean energy and to address housing quality shortfalls. Tariffed on bill programs provide capital for home upgrades with repayments provided by the energy savings from upgrades performed. Because these programs are tied to the electric meter, not to an individual, they are available for renters or owners. Atlanta Housing is working with the Solar and Energy Loan Fund (SELF) to provide unsecured loans up to $25,000 to eligible landlords for energy efficiency and clean energy upgrades, paired with a rent boost up to $175 per month to offset loan payments. SEEA’s Room to Breathe program – a partnership with the Atlanta Volunteer Lawyers’ Foundation (AVLF) and SK Collaborative – also provides a model for innovative partnerships that can support tenants in addressing deferred maintenance and securing healthy housing.

Each of these provides key opportunities for leveraging energy efficiency funding to support the millions of renters in the South who struggle with housing insecurity by addressing deferred maintenance. But housing instability is multifaceted, and to address it at scale resources for tenants and landlords must be combined with robust tenant protections.

September Map of the Month

By Laura Diaz-Villaquiran

Data: Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) EAGLE-I Power Outage Dataset

** Click on the map image to see the time series.**

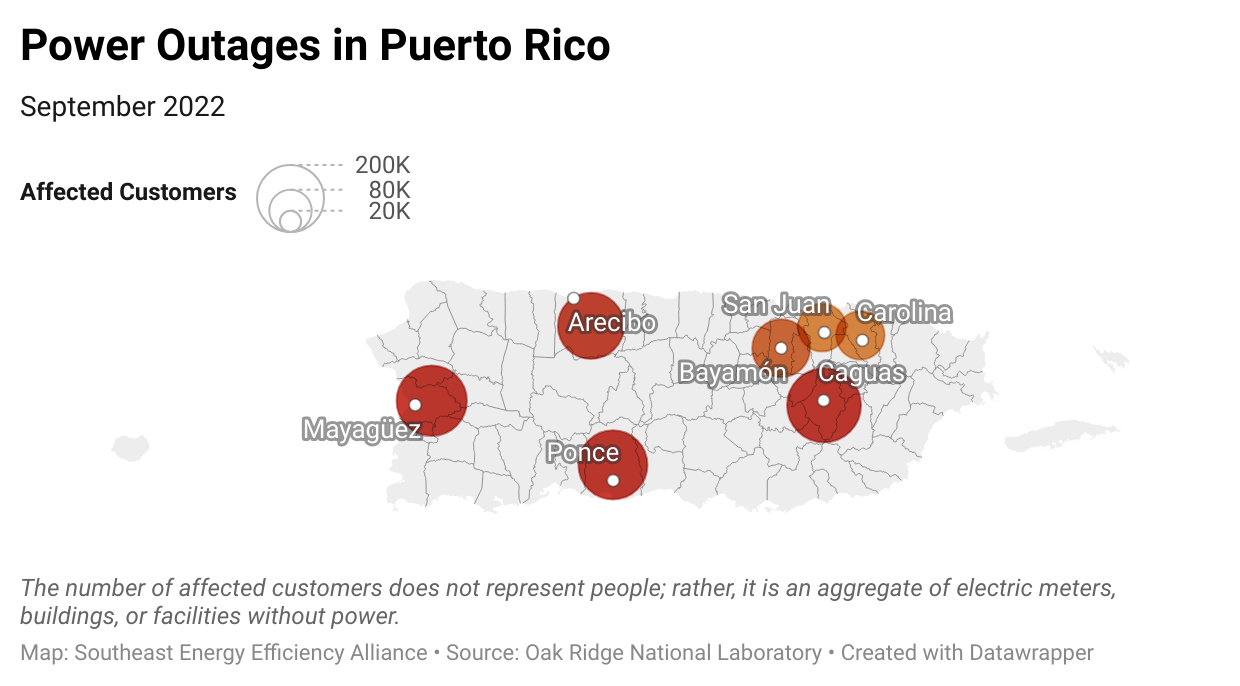

In recent years, Puerto Rico has struggled with persistent power outages, and as we find ourselves in the middle of hurricane season, the island’s energy challenges—and resiliency solutions—are more pressing than ever. This month’s map features a time series of blackouts in Puerto Rico during 2022, using the most recent data available.

The data used for this analysis comes from Oak Ridge National Laboratory’s EAGLE-I power outage data, which focuses on Puerto Rico’s most populous municipalities. The 2022 data shows that the island experienced persistent energy outages throughout the year, with a spike in power loss following Hurricane Fiona’s landfall on September 18th, 2022. Note that the legend in the map does not indicate the number of people affected, it is the number of electric meters, buildings, or facilities without power.

Puerto Rico has endured devastating natural disasters, including Hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017, which led to a collapse of the island’s energy grid. After being impacted by both storms, 80% of the grid was destroyed, seriously affecting the island’s energy generation, distribution, and transmission infrastructure. This was considered the “largest blackout in U.S. history” and the world’s “second largest” blackout.

In 2020, the island experienced a magnitude 6.4 earthquake which caused further disruptions to the energy grid, damaging Costa Sur, the largest power plant. In June of this year, a blackout during a heat wave left over 350,000 customers without power. Puerto Rico’s grid instability is of serious concern as it threatens the health and safety of its residents and puts a strain on critical services.

According to the EIA, Puerto Rico imports the majority of the energy that it consumes and relies on 94% of fossil fuels to generate most of the island’s electricity. This reliance on imports and non-renewable energy makes it so that Puerto Ricans pay some of the highest energy prices in the U.S.

Despite the ongoing challenges with Puerto Rico’s power grid, the island’s favorable conditions for solar, wind, and geothermal energy provide promising opportunities for building a more resilient and sustainable energy system. Some of the proposed pathways for leveraging climate resilience, emergency preparedness, and energy security in Puerto Rico include:

- Puerto Rico’s Energy Resilience Fund – The U.S. Department of Energy has committed $325 million in funding opportunities to support Puerto Rico’s energy grid modernization and clean energy transformation.

- Energy grid transformation – One of the key priorities of the Puerto Rican government’s energy policy is to move toward 100% renewable energy by 2050 and reduce the island’s dependence on fuel imports. This initiative is outlined in Ley 17-2019, also known as the “Ley de Política Pública Energética de Puerto Rico.”

- Increased Demand response capability: conducting targeted load shedding which would allow for load monitoring during emergencies.

- Solar powered microgrids: Solar microgrids and battery storage projects are underway. Microgrids are localized energy generation systems that operate independently from the main power grid and can provide electricity during a grid failure.

- Solar for All: The federal government has allocated funding for subsidized solar for low-median-income households. To learn more visit: U.S. Department of Energy’s Solar Access Program.

These policy priorities aim to decrease Puerto Rico’s reliance on imported fossil fuels, leverage emergency preparedness, and enhance energy affordability. SEEA is committed to working with Puerto Rico in leveraging local capacity to support these and other efforts to enhance the resilience of the island’s energy infrastructure.

August Map of the Month

By: Hanka Kirby

Source: LIHEAP Data Warehouse

States in the Southeast have some of the highest rates of energy insecurity in the country, as we noted in a previous post. Because of this, energy assistance and weatherization programs available from local, state, federal, and utility sources are critical sources of support for thousands of households in the region who struggle to pay their energy bills.

One of the most vital programs is the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), managed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), which since 1981 has provided financial assistance for low-income households to help prevent utility disconnections and assist with heating and cooling homes. According to the National Energy Assistance Directors’ Association (NEADA), nearly one-third of LIHEAP-eligible households reported forgoing food to pay their utility bills, 40% had sacrificed medical care, and one-fourth had someone fall ill because their home was too cold. To meet these critical needs, LIHEAP provides a range of support, including financial help for heating, cooling, crisis, and weatherization assistance, in addition to other services that reduce energy burden.

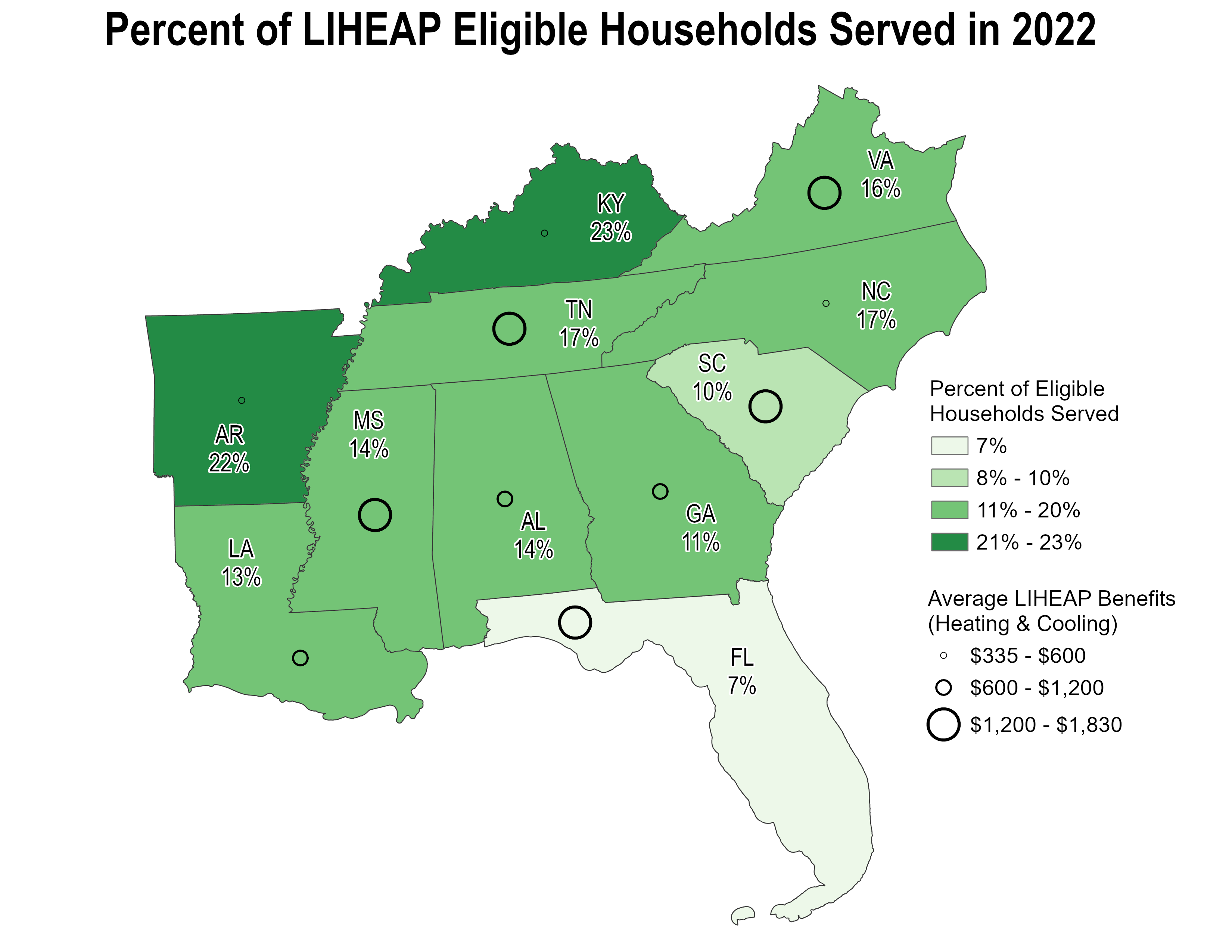

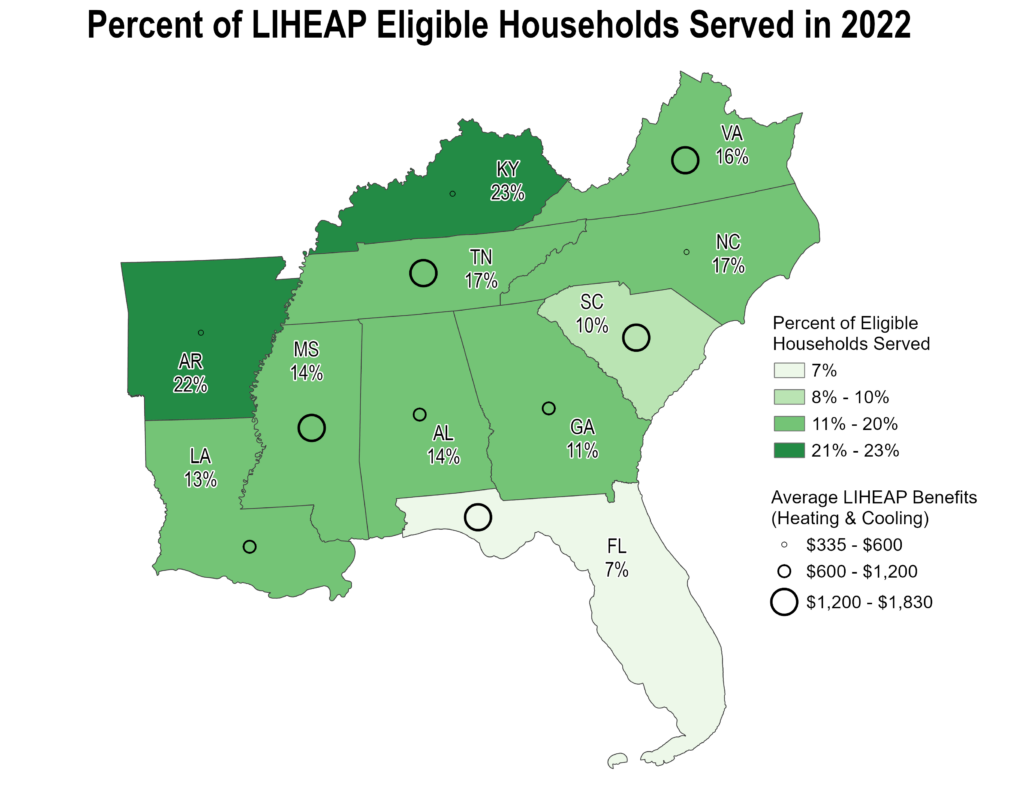

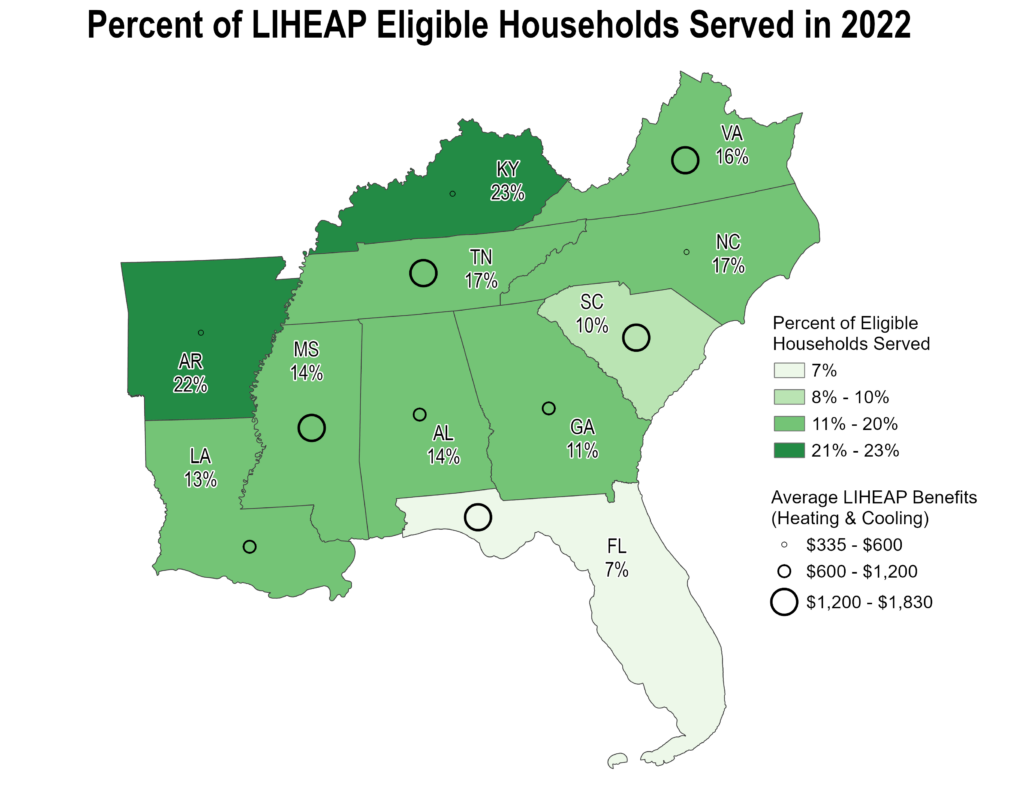

This month’s maps use data from the LIHEAP Data Warehouse to shed light on the scope and impact of LIHEAP assistance in the Southeast. Through LIHEAP, HHS makes grants to states, tribes, and territories that are typically administered through local community action agencies. However, the need far exceeds the resources available and local agencies often must make difficult decisions about how to distribute funds.

As the map shows, LIHEAP reached 15% of eligible households in the Southeast on average. This ranges from Arkansas and Kentucky, which served 22% and 23% of their qualified households, respectively, to Florida, which served 7% of the eligible population. Variation in state aid sheds light on the difficult policy tradeoff between “maximizing the number of households that receive funding and maximizing the level of benefits each household receives.”

LIHEAP gives flexibility to grantees, allowing states to decide how to allocate funds. While some states like Florida, Mississippi, and South Carolina opt to provide a higher level of benefit, others, including Arkansas, Kentucky, and North Carolina, provide lower benefit levels but reach a greater proportion of eligible households. One study found that LIHEAP tends to benefit “marginally energy insecure households more than severely energy insecure,” though this may also be because households with more resources can more easily navigate assistance applications. While the variation between states can make it difficult to draw universal conclusions about LIHEAP, the flexible nature of the program allows each state to tailor its approach to its specific needs.

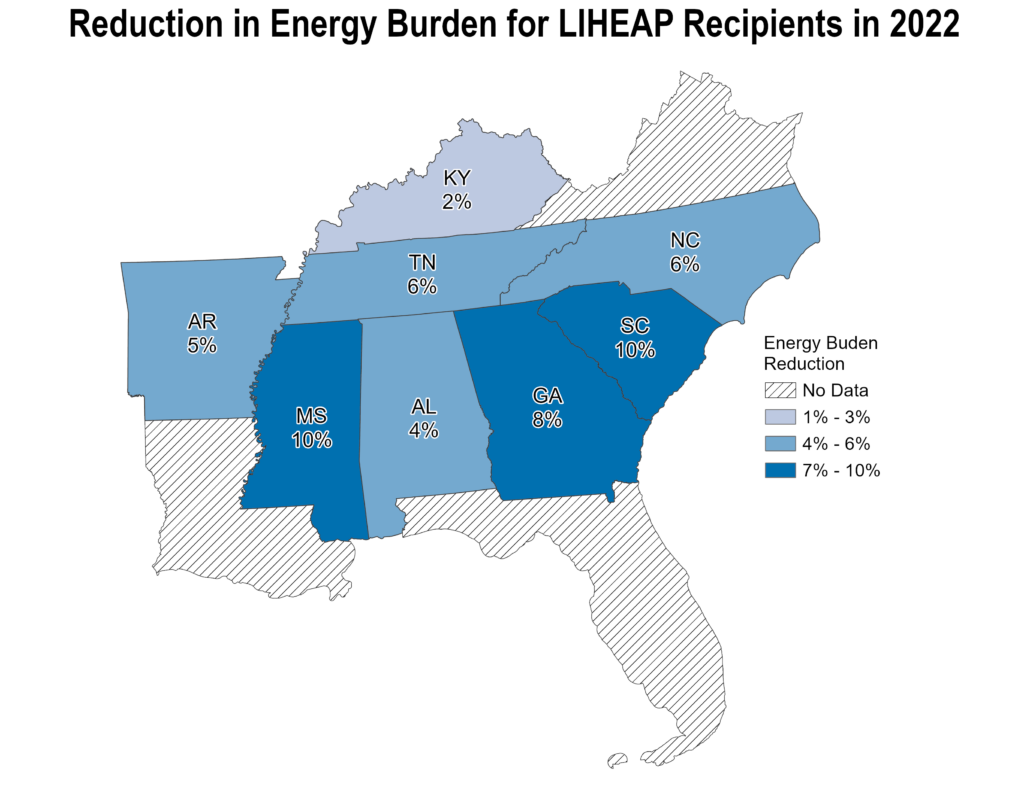

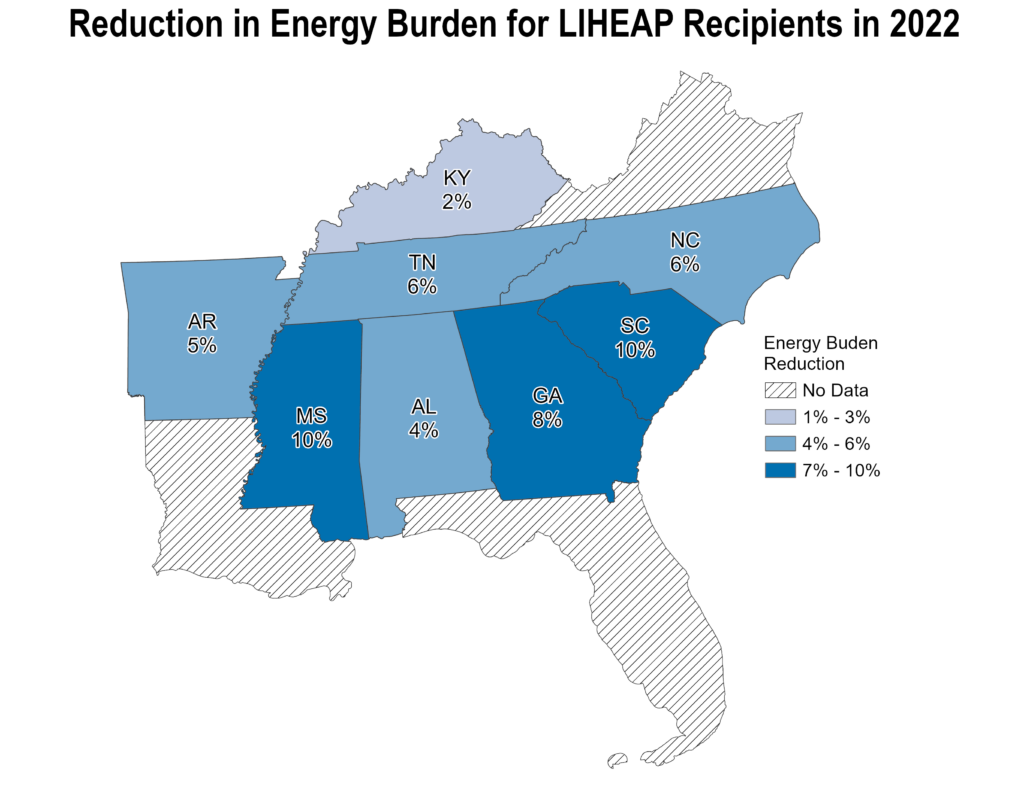

What is clear is that there have been real benefits for the households that were served. In FY23, the most recent data available, 1.2 million households in the South received some form of LIHEAP assistance. The loss of power due to a utility disconnection was averted or resolved more than 3.2 million times. In the Southeast, participating households had a 6% reduction in energy burden on average, with South Carolina and Mississippi having an average energy burden reduction of 10%. This support helps reduce energy insecurity, prevent dangerous health impacts, and promote resiliency for millions of families.

Perhaps the largest reason for the small percentage of eligible households reached is simply the level of program funding. As energy costs rise, so have the number of people who struggle to pay their utility bills. Existing LIHEAP funding cannot keep up with demand. Many states and community action agencies have focused assistance on the most vulnerable households: those with seniors, disabilities, and children under the age of five.

The program works, yet a substantial portion of the eligible population cannot be reached without expanded funding. LIHEAP provides life-critical heating and cooling support. It protects those most susceptible to extreme heat and cold, prevents dangerous health impacts, and promotes resiliency. As energy costs and extreme weather events rise, it is critical to recognize how year-round heating and cooling assistance become increasingly necessary, and how LIHEAP can work in concert with weatherization assistance to support vulnerable communities.

July Map of the Month

By Grace Parker

Source: Alternative Fuels Data Center and EV Hub

Historically, the development of transportation infrastructure in the United States has exacerbated inequities by displacing people of color and contributing to residential segregation. Without thoughtful approaches, the build-out of electric vehicle (EV) infrastructure has the potential to contribute to inequities through access and affordability disparities. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) provides funding to build 500,000 public EV chargers by 2030. Where these chargers are sited will play a key role in determining who can drive an EV and where air pollution is reduced.

In 2021, a MIT study reported that EV buyers were “mostly male, high-income, highly educated, homeowners, who have multiple vehicles in their household, and have access to charging at home.” The barriers to greater EV adoption are multidimensional, but expanded public charging access can make EVs a compelling option, particularly for renters and residents in multifamily housing who are unable to install charging equipment. Many stakeholders have a role in siting public EV chargers, including local governments, state transportation agencies, utilities, and private property owners, and all can play a role in making EV chargers more accessible.

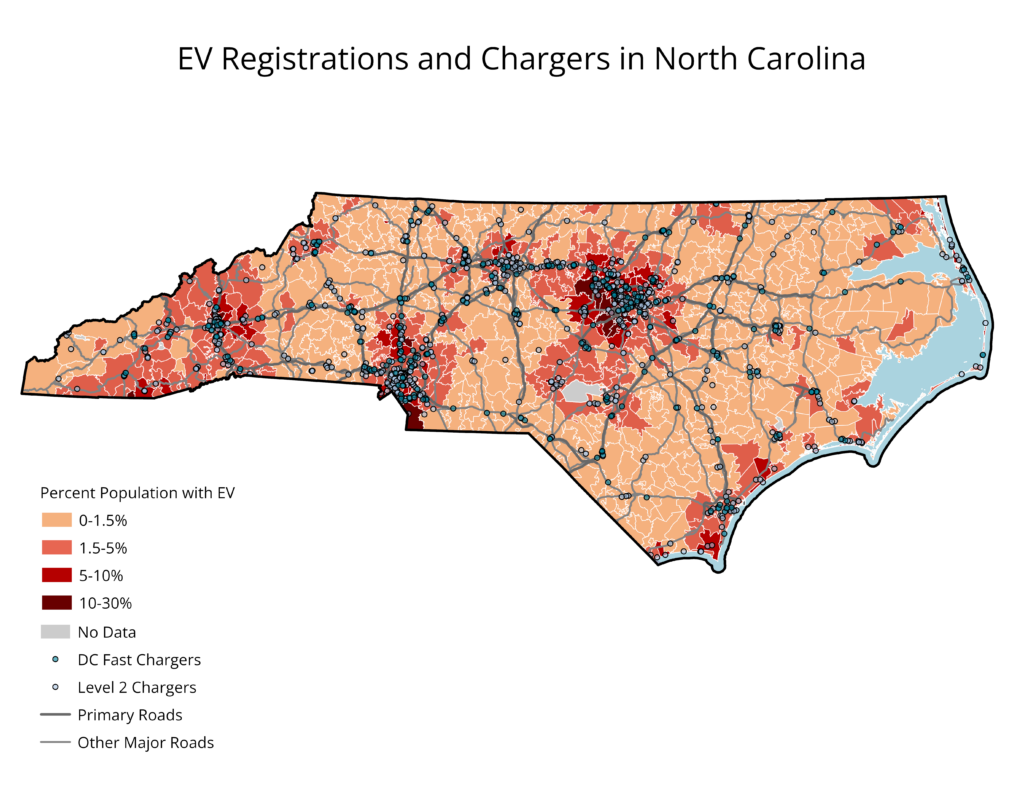

Using data from the Alternative Fuels Data Center and Atlas Public Policy’s EV Hub, this month’s map shows that EV registrations are highly correlated with the number of public EV chargers. The roughly 1,650 public level 2 and fast charging stations in North Carolina and the areas of greatest EV adoption are both centered in the state’s most population-dense areas, including the Research Triangle, Charlotte, and the Piedmont Triad.

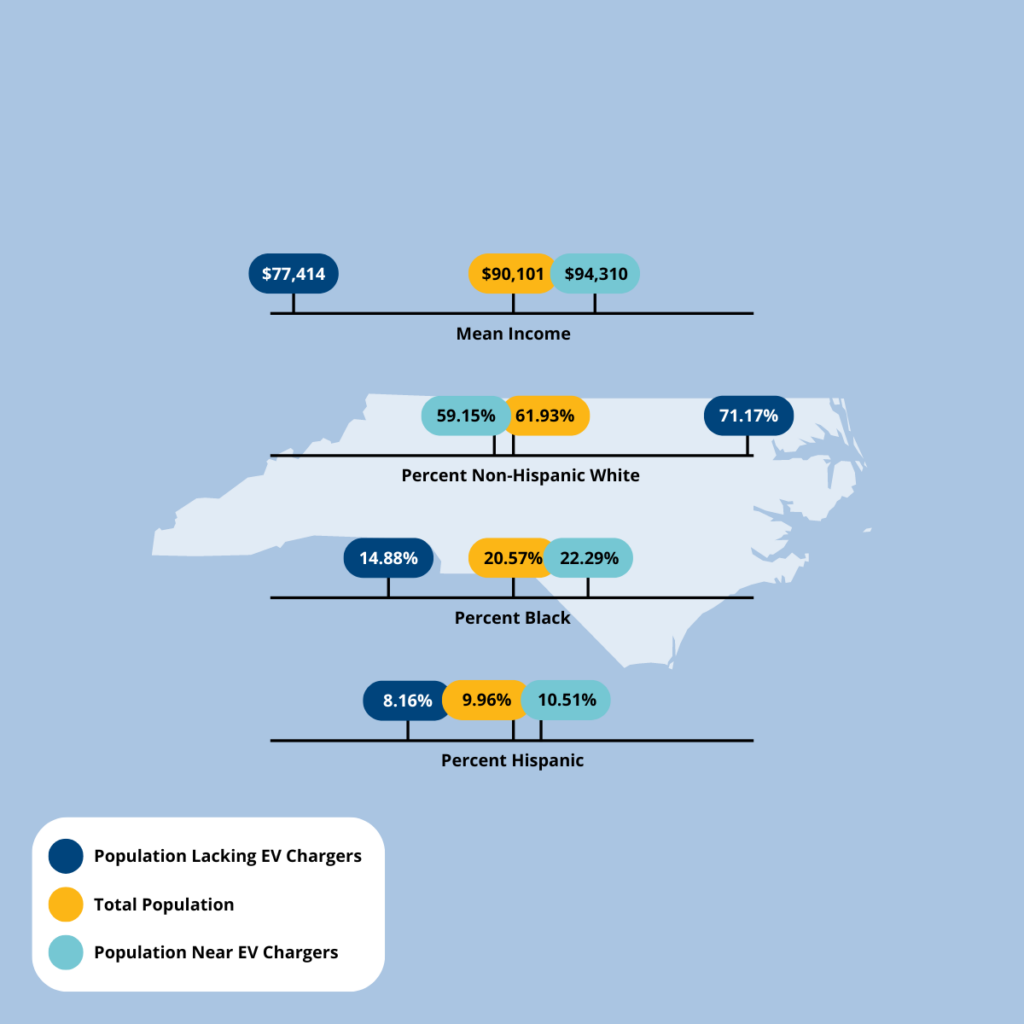

About 23% of the state’s population lives in a charging desert, which we define here as more than five miles from the nearest public charger. We found that this population had a significantly lower mean income of about $77,400 than the population overall at $90,100. While it is well-documented in other areas that people of color have less access to public chargers, at this scale we found that the population with charging access had higher proportions of Black and non-white Hispanic residents than the general population and those without charging access. This might be due to the urban-rural differences in racial composition, prioritization of equity in EV charger siting, or simply the geographic scale at which we did this analysis.

Many barriers to EV charging access cannot be captured by location, including the need for a smartphone or a subscription and associated costs such as expensive garages. Even where public charging is common, it can be 2-4 times more expensive than at-home charging, making it comparable to fuel costs for vehicles with internal combustion engines, and cutting into the fuel savings that make EVs a competitive purchase.

It’s crucial that, while building out public infrastructure, policies also prioritize at-home charging and EV purchase incentives. A variety of approaches have been implemented nationally to extend EV adoption to lower-income and multifamily building residents. Beginning January 1, 2024, the federal $7,500 tax credit was made available at the point of sale, extending it to lower-income households with less tax liability. Some states and utilities have set aside rebates specifically for multifamily property owners or low-income households. These policies help ensure that funding is directed to those for whom it is most impactful.