Category: Federal

Tracking Federal Spending in the Southeast and U.S. Territories

Grace Parker

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, also known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), passed in November 2021. The law allocates $550 billion in new federal spending over ten years for infrastructure projects, including roads, public transit, broadband, and electric grid upgrades. With so much funding on the table, SEEA is working to ensure funds are distributed equitably across the U.S. and to underserved communities. To this end, SEEA tracked and analyzed where BIL funding has been committed, what it’s being used for, and what type of funding it is. We have published our findings in two new whitepapers, “Investing in the Southeast” and “Investing in the Territories,” with accompanying data dashboards for states and territories.

We found that the Southeast has not received a share of funding proportionate to its population. Nationally, the BIL had committed, on average, $537 per person as of January 22, 2024, compared to just $443 per person in the Southeast. For BIL grant funding, south-central (Texas and Oklahoma) and southeastern states received just $38 and $43 per person, respectively, while northeastern states received $124 per person on average. Southeastern states received funding primarily through formula funds, which are noncompetitive allocations to states and territories based on distribution formulas.

In the U.S. territories, funding for Puerto Rico contrasts starkly with other territories. Given that Puerto Rico has nearly 3.2 million people – twenty times more than Guam, the next most populous territory – it’s not surprising that Puerto Rico receives over nine times more funding than the other territories at over $650 million. However, Puerto Rico still receives a low amount of funding per capita at just $202. Although committed funding in the other territories is less than $100 million each, funding per capita matches or outpaces that of Puerto Rico and many U.S. states, with the Northern Mariana Islands and American Samoa receiving $1,553 and $1,044 per person, respectively. Unlike the Southeast, the U.S. territories receive most of their funding through competitive grants. The greater dependence on grants is notable, given the capacity required to develop competitive grant applications.

While the BIL updates the definition of infrastructure to include critical energy and environmental investments to mitigate climate change, BIL investments have so far been focused on traditional infrastructure like roads and bridges. Ground transportation is the largest category of funding in the BIL, and nearly 75% of BIL funding in the Southeast is for ground transportation. Other key categories include broadband expansion and pollution control. Puerto Rico also received the largest share of funds for ground transportation followed by pollution control and broadband, whereas other territories received most of their funding for pollution control with ground transportation comprising only about a quarter of funding. Energy conservation funding, which is dedicated primarily to the Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP) and State Energy Program (SEP), comprises about 3.1% of committed BIL funding in the Southeast and about 2.4% in the territories.

This analysis is the first installment in an annual review of federal funding, which will help SEEA identify gaps in federal support for the Southeast states and U.S. Island Territories. To see how BIL funding in your state or territory stacks up, check out our associated whitepapers and data dashboards.

Map of the Month – September

Grace Parker

Map: Southeast Energy Efficiency Alliance

Map: Southeast Energy Efficiency Alliance

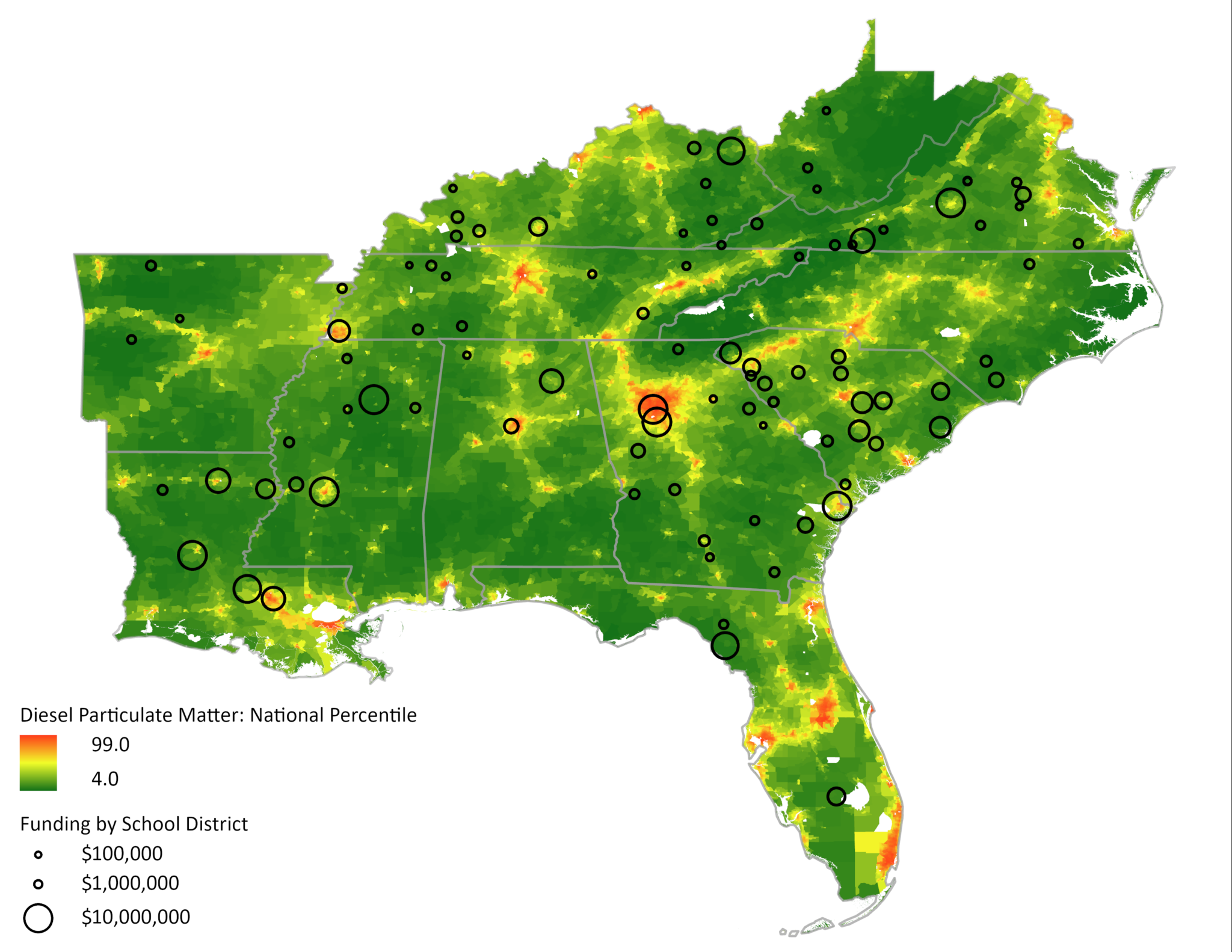

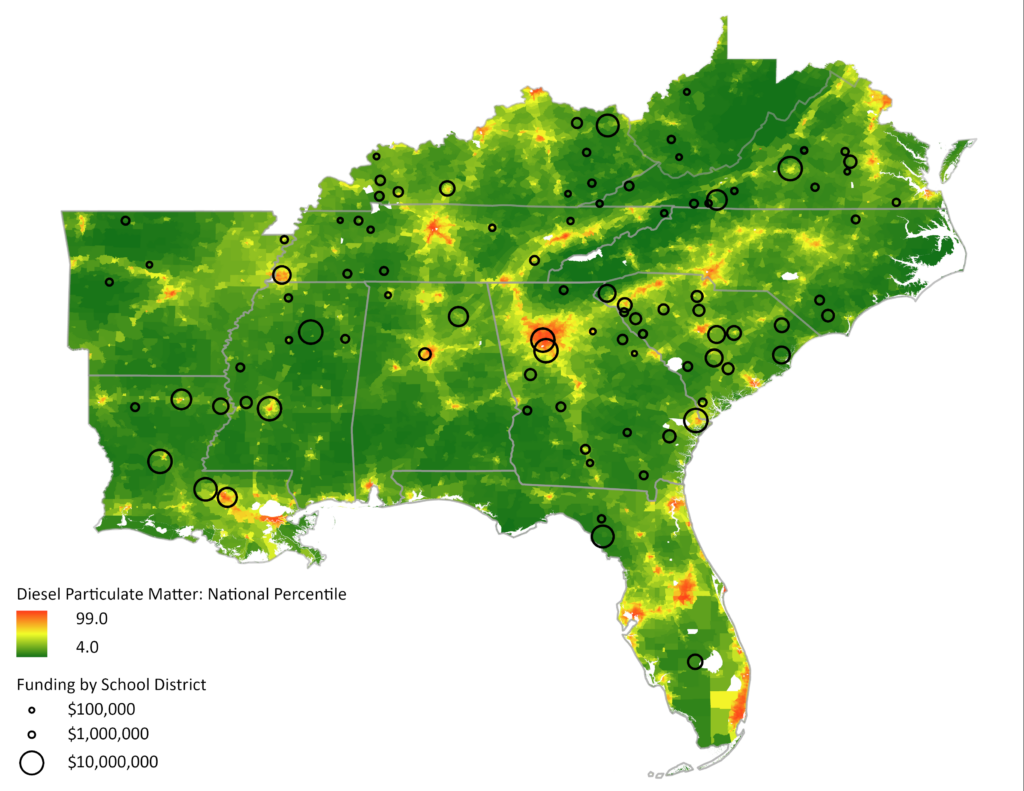

The EPA’s Clean School Bus Program aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and exposure to air pollution by replacing older school buses with low-emission and zero-emission models. Has that funding reached the communities most impacted by the harmful effects of diesel school buses? Diesel buses produce diesel particulate, which has been linked to an increased risk of asthma and cancer. A part of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the Clean School Bus Program provides funding to school districts to purchase new low-emission and zero-emission buses. This funding supports a global reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, local air quality improvements, and health benefits to nearby communities.

This month’s maps show that the school districts that were awarded program funding in 2023 are generally more rural, have high student poverty rates and lower levels of diesel particulate, especially compared to more urban districts. The EPA prioritizes funding for rural school districts, high-need local education agencies, and schools that serve residents of Native American lands. High-need local education agencies include districts where 20 percent or more of students served are from low-income families. The student poverty map shows that most of the funding went to these districts. The Clean School Bus Program largely supports schools that have smaller budgets and serve students from lower-income communities.

This month’s maps reveal a tension between funding districts that have the most difficulty paying for clean school buses and funding districts with the highest diesel particulate pollution. However, we can target funding to areas that need support to overcome both of these challenges, like New Orleans. Although a district with similar needs in Birmingham received a $3.6 million grant, New Orleans districts did not. School districts seeking cleaner air and better health for their communities need additional outreach and technical assistance to support their funding applications to the Clean School Bus Program. By focusing on districts that face multiple obstacles to their achieving their goals, we can deepen the impact of this historic and critical funding.

2022 Election Highlights

Updated December 21, 2022

The Inflation Reduction Act, passed in August 2022, preceded by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which passed at the end of 2021 invest billions of dollars into the United States’ energy infrastructure to aid in the transition to low-carbon energy sources. The distribution and impact of this historic funding opportunity will be influenced by the federal, state and local leaders chosen to represent the Southeast in the 2022 midterm elections.

Gubernatorial Elections

Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia and Tennessee held elections this year to determine their next governor.

In Alabama, Democratic candidate Yolanda Flowers challenged incumbent Republican candidate Kay Ivey on the ballot. Voters reelected Ivey to serve another term. Governor Ivey recently supported the opening of an EV battery plant in Montgomery, which is aimed to help supply batteries to a Hyundai Plant in Montgomery and Georgia’s Kia Plant.

Arkansas’s gubernatorial election received national attention due to the name recognition of Republican candidate, Sarah Huckabee Sanders. Sanders was White House press secretary under President Donald Trump and her father, Mike Huckabee, was governor of Arkansas from 1996 – 2007. Sarah Huckabee Sanders ran and won against Democrat Chris Jones and Libertarian Ricky Dale Harrington Jr.

Florida’s incumbent candidate for governor, Republican Ron DeSantis, made headlines earlier this year for his veto of a utility supported bill which would prevent net metering. This move garnered support from the solar industry. DeSantis was joined on the ballot this year by former governor of Florida and U.S. Representative Charlie Crist who voted for the Inflation Reduction Act and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law as a member of Congress. DeSantis was reelected to serve a second term as Governor of Florida.

Democratic candidate Stacey Abrams and Republican incumbent Brian Kemp were both on the ballot for governor of Georgia this year. Brian Kemp was reelected to serve another term. During Governor Kemp’s term, relevant projects to the energy industry included the expansion of the Qcells solar plant, an additional investment of $150 million into solar projects, bringing SK Battery America into the state and employing Georgia veterans, as well as bringing major EV manufacturer Rivian into the state.

In Tennessee, citizens chose between current Republican Governor Bill Lee, Democratic candidate Dr. Jason Martin and eight other independents. Governor Bill Lee was reelected. His campaign’s priorities included quality education, economic development, safety and supporting families. His campaign website does not mention his stance on energy or climate change.

Mayoral Elections in State Capitals

Three elections for mayor occurred in state capitals across the Southeast. Frank Scott Jr., the first Black mayor of Little Rock, Arkansas was reelected to serve another term. In March 2022, Scott set a goal to have 100% of city operations run on renewable energy by 2030. The incumbent mayor of Tallahassee, Florida, John Dailey, won reelection. Mayor Dailey has committed to 100% renewable energy in the city by 2050 by implementing energy efficient measures, use solar energy in city buildings, and investing in electric fleet transition. He has worked to expand solar fields at airports and increased the number of city-owned buildings powered by solar. The mayor of Raleigh, North Carolina, Mary-Ann Baldwin, was reelected to serve a second term. During her first term as mayor, she helped develop a Community Climate Action Plan which includes goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 80% by 2050 through a combination of electric vehicle fleet transition, energy efficiency in buildings, and supporting renewable energy in the city.

Senate Elections

Three Senate races in the Southeast will impact future state of climate and energy policy.

Florida citizens reelected incumbent Republican candidate Senator Marco Rubio versus Democratic candidate Val Demings. Rubio voted against the Inflation Reduction Act and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill but helped pass major legislation in 2008 which gave states the authority to develop renewable energy portfolio standards.

In Georgia, Republican candidate Herschel Walker ran against the incumbent senator Reverend Raphael Warnock. As senator, Warnock supported the Solar Energy Manufacturing for America Act, expanding access to electric charging infrastructure by securing $20 million in grants for this project funding, brought electric school buses to the state, and helped limit the costs that small businesses and rural families pay for electricity. On December 6, Senator Warnock was reelected in the runoff election.

In North Carolina, voters chose between Democrat Cheri Beasley and former U.S. Representative, Republican Ted Budd. Budd was elected to serve as the next senator from North Carolina. In 2021, Ted Budd proposed an amendment to the partisan coined “Green New Deal” which would defund $100 million in environmental justice grants.

Regulatory Commission Elections and Appointments

This fall, in states where public service commissioners are not appointed by governors or other legislative bodies, the public voted for commissioners to represent their districts. These positions are critically important as it is their responsibility to regulate the price that consumers pay for electricity, oversee processes for utilities such as integrated resource planning and approve utility energy efficiency measures and programs.

In Alabama, Place 1 and Place 2 seats were up for reelection. Incumbents, Jeremy Oden and Chris Beeker both were reelected this fall to serve additional four-year terms after winning majority vote against their running mates. There is still one vacancy to fill on this commission. In Louisiana, two commissioner seats were on the ballot this fall, winning the majority in the primary vote, incumbent Mike Francis was reelected in District 4. In the general election on December 10, Davante Lewis was elected to serve as District 3’s next commissioner, unseating Lambert Boissiere III who previously held the seat for 18 years. Lewis intends to address resiliency, investments in renewable energy and the high fees residents pay for late utility payments.

In Arkansas, Katie Anderson was appointed to fill a vacancy in the commission by Governor Hutchinson. In July, Governor Beshear appointed Mary Pat Regan to Kentucky’s public service commission. On May 2, 2022, North Carolina Governor, Roy Cooper appointed Karen Kemerait to the commission. In Tennessee, Commissioner David Crowell was appointed to the commissioner by Speaker of the House Cameron Sexton and Dr. Clay R. Good was also appointed to the commission by Lieutenant Governor Randy McNally.

There is one vacancy on Virginia’s commission this year, this spot should be filled by the General Assembly. The Tennessee Valley Authority Board of Directors has four vacancies. Typically, this board operates with nine directors, however only five are currently serving while three Biden nominees await approval by the Senate. In South Carolina the General Assembly selects commissioners. This year they will select replacements for both Tom Ervin and Justin T. Williams of Districts 4 and 6 whose terms have expired.

Georgia’s public service commission election gained national attention this year because of a 2020 lawsuit challenging the voting method used to elect commissioners. The lawsuit was filed by the Georgia Conservation Voters, Black Voters Matter and the NAACP claims the state’s voting method violates Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act and dilutes Black votes. The current voting method allows voters from all over the state to elect commissioners for at-large districts rather than selecting a commissioner to represent regional districts. On August 19, the Supreme Court overturned an order from the Circuit Court of Appeals which would have allowed public service commission elections to occur as normal on election day. As of now, elections are paused and commissioners up for reelection will retain their positions as the case continues in 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Legislation

Virginia

- SB290: This bill was passed by the state Senate in February but defeated by the House later that month. It refers to a new requirement that would have required all newly constructed legislative buildings starting in January of 2023 and over 5,000 square feet must have roofs that are compatible with solar panels, cool, or energy efficient.

- HB 73: The state House of Representatives and Senate passed this bill in February which is intended to remove energy efficiency pilot programs as topics of public interest , as well as, removing capacity requirements for renewable energy facilities.

- Executive Order 9: In January, Governor of Virginia signed an executive order which calls to re-evaluate Virginia’s participation in Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) and engage in the process to end it.

2023 Legislative Session Schedule

| State | Legislative Session Convenes | Legislative Session Adjourns (all dates are estimates) |

| Alabama | January 9 | April 30 |

| Arkansas | January 9 | March 15 |

| Florida | March 7 | May 5 |

| Georgia | January 9 | April 2 |

| Kentucky | January 3 | April 13 |

| Louisiana | April 10 | June 5 |

| Mississippi | January 3 | April 4 |

| North Carolina | January 11 | June 30 |

| South Carolina | January 10 | June 30 |

| Tennessee | January 10 | April 26 |

| Virginia | January 11 | February 15 |

SEEA’s State Utility Profiles provide additional information on utility regulation and energy efficiency planning in the Southeast. Questions? Contact Claudette Ayanaba, policy manager.

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act will transform the Southeast

On Friday, November 5, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. The bill passed the Senate in a bipartisan vote in August and President Biden has planned a signing ceremony for the bill on Monday, November 15. The $1.2 trillion package is a historic investment in infrastructure that advances energy efficiency, resiliency, and electric transportation. Combined with the President’s Build Back Framework, it will average 1.5 million additional jobs every year for the next 10 years.

More than $4.5 billion will be appropriated to the U.S. Department of Energy to fund vital energy efficiency programs such as the State Energy Program, Weatherization Assistance Program, and the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Block Grant Program. The act also dedicates more than $30 billion to electrifying transportation from personal vehicles to school buses, ports, and public transit. Supporting energy efficiency and electric transportation is especially important as we continue to recover from the covid-19 pandemic, while also addressing the impacts of climate change like stronger storms, extreme heat, and rising sea levels in the eleven southeastern states SEEA serves.

“These investments are critical as we harness the power of energy efficiency to transform the way we live, work, and thrive in the Southeast and nationally,” says SEEA president, Aimee Skrzekut. “We have an unprecedented opportunity to invest in a more diverse workforce, a more robust economy, and healthier housing to create a prosperous future for all.”

Key provisions in the bill include:

Energy Efficiency

- An online database to track energy demand, generation, storage, and emissions where available, in the contiguous 48 states (Title IV – Enabling Energy Infrastructure Investment and Data Collection, Subtitle B – Energy Information Administration);

- A new grant program to support the adaptation and implementation of updated building energy codes, which is estimated to save over $40 billion and 1,180 MMT of CO2 emissions over the next thirty years. (Title V – Energy Efficiency and Building Infrastructure, Subtitle B – Buildings, Section 40511);

- $10 million to educate and train workers on energy-efficient, modern building technology (Title V – Energy Efficiency and Building Infrastructure, Subtitle B – Buildings, Sections 40512 and 40513);

- A $250 million for a new revolving loan fund, Investing in New Strategies for Upgrading Lower Attaining Efficiency (INSULATE) that supports residential and commercial building energy audits and improvements prioritized in states with the poorest efficiency in buildings (Title V – Energy Efficiency and Building Infrastructure, Subtitle A – Residential and Commercial Energy Efficiency, Section 40502);

- Funding to support energy efficiency improvements and renewable energy improvements at public school facilities and nonprofit buildings (Title V – Energy Efficiency and Building Infrastructure, Subtitle D – Schools and Nonprofits);

- An Energy Jobs Council to oversee the National Energy Employment Report and related activities (Title V – Energy Efficiency and Building Infrastructure, Subtitle E – Miscellaneous); and

- Advancing industrial energy efficiency and smart manufacturing (Title V – Energy Efficiency and Building Infrastructure, Subtitle C – Industrial Energy Efficiency).

Resiliency

- A requirement that state regulators consider establishing rate mechanisms allowing utilities to recover costs associated with programs that promote demand response (Title I – Grid Infrastructure and Resiliency, Subtitle – A Grid Infrastructure and Reliability, Section 40104);

- Federal assistance to establish state energy security plans that protect energy infrastructure against physical and cybersecurity threats and ensure resiliency (Title I – Grid Infrastructure and Resiliency, Subtitle A – Grid Infrastructure and Reliability, Section 40108);

- Funding to research the application of codes and standards for the use of mobile and stationary batteries in flexible applications (Title I – Grid Infrastructure and Resiliency, Subtitle A – Grid Infrastructure and Reliability, Section 40111);

- Funding to research second-life applications for electric vehicle batteries as energy storage solutions (Title I – Grid Infrastructure and Resiliency, Subtitle A – Grid Infrastructure and Reliability, Section 40112); and

- Help for coastal Georgians to prepare for more extreme weather, coastal flooding and other disasters exacerbated by climate change.

Electric Transportation

- $2.5 billion to fund electric vehicle charging infrastructure in rural areas, low-and moderate-income neighborhoods, and communities with less public parking options (Title I – Federal-Aid Highways, Subtitle D – Climate Change, Section 11401);

- An Electric Vehicle Working Group of government, utilities, and manufacturers to report on the barriers to electric vehicle adoption (Title V – Research and Innovation, Section 25006);

- More than $6 billion to support a domestic supply chain for battery production (Title II – Supply Chains for Clean Energy Technologies, Section 40207);

- A requirement that state regulators consider measures to promote electric transportation adoption by improving charging infrastructure (Title IV – Enabling Energy Infrastructure Investment and Data Collection, Subtitle C- Miscellaneous, Section 40431);

- $5 billion to establishes a new grant program to replace existing school buses with zero or lower emission buses (Title XI – Clean School Buses and Ferries, Section 71101);

- Investment to expand electric vehicle charging stations and other zero emission initiatives in North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia; and

- Funding to replace the ridesharing transit fleet with zero-emissions vehicles in Gainesville, FL.

Additional Resources

- H.R. 3684 (Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act), Full Text

- Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act Fact Sheet, Alliance to Save Energy, August 2021

- Summary of EV-Related Provisions in Senate Version of H.R. 3684 – Atlas Public Policy, October 13, 2021

- Legislative Analysis for Counties, the Infrastructure Investment & Jobs Act, National Association of Counties, November 7, 2021

- Ready-to-Go: State and Local Efforts Advancing Energy Efficiency Toolkit, American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, November 9, 2021

We will continue to track resources and opportunities as they are deployed nationally, and at the state or municipal level. If you want to explore the provisions of the bill further or would like to know how your organization can get involved, email or schedule a call with Cyrus Bhedwar, director of energy efficiency policy.

All the places we’ll go – clean cars, trucks, buses, and jobs!

Anne Blair

America loves to drive. There are nearly 280 million vehicles on the road and the average person drives around 13,500 miles a year. The demand for transportation accounts for $1.9 trillion, or 9.1% of the GDP. We spend more money on transportation than we do on education ($1.4 trillion [6.5%]) and nearly as much as we do on food ($2 trillion [9.4%]). Our car-loving culture and transit-driven economy comes at a price beyond what we spend on vehicles and the gas that powers them. Our current system’s focus on personal, internal-combustion engine vehicles for every American was fueled by the creation of the interstate highway system in the 1950s and ‘60s. That sweeping infrastructure investment came at the expense of downtown, majority Black communities, and reliable mass transit systems in most American cities. Currently, just 3% of the trips Americans take are by mass transit.

Transportation is also the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the United States. Those emissions contribute to a warmer climate, higher rates of heat-related and respiratory illness, more severe weather, and sea level rise among other things. These factors increase the cost of healthcare, insurance, and housing. In the Southeast, the impacts of climate change are more disproportionately felt in low-income and Black communities. These neighborhoods are often bordered by transit corridors and lag in green infrastructure compared to wealthier or white counterparts.

Even accounting for emissions created by generating electricity, plug-in electric vehicles (EVs) are still three times cleaner than comparable gasoline-powered vehicles. However, there are only 1.8 million EVs currently registered in the U.S., representing less than 2% of all vehicles on the road. The U.S. market share of EVs is a fraction of the Chinese market and China has eight times as many charging points for EVs than America. With strategic investment, the U.S. has an opportunity to lead in EV manufacturing, infrastructure, drive down the price of EVs, increase demand, and create jobs.

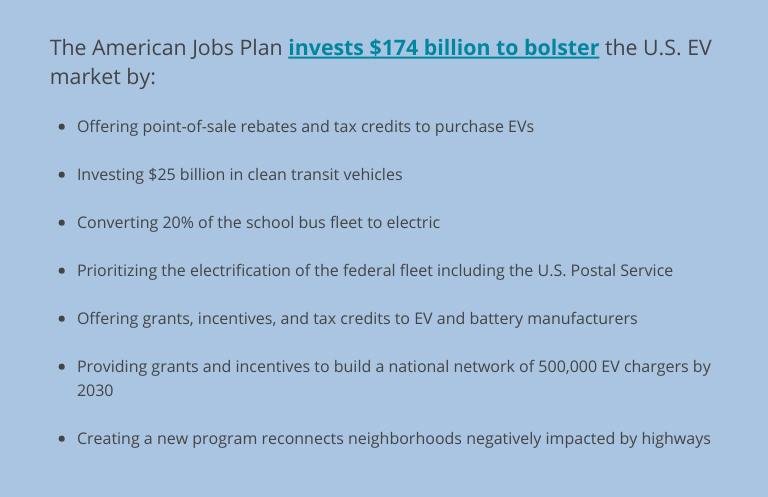

The American Jobs Plan proposes expanding availability and access to energy efficient transportation by investing in a strong domestic supply chain for EVs and parts, growing the market for EVs, building a national network of charging infrastructure, creating an equitable and modern public transit system, and reconnecting communities that were purposefully divided by highway projects.

In the Southeast, EVs are revitalizing existing manufacturing infrastructure by adapting operations, or inviting new business. Blue Bird is making electric school buses in Fort Valley, GA; SK Innovation is building two battery facilities and just announced a joint venture with Ford Motor; Mercedes-Benz announced its Tuscaloosa County plant will start producing electric SUVs in 2022; Schnellecke Logistics Alabama is adding a new warehouse and jobs to support Mercedes-Benz; in Spring Hill, TN, GM is transitioning its existing plant to build electric vehicles and recently announced Ultium Cells LLC, a joint battery cell venture with LG Energy Solution; battery maker Microvast is building a new factory in Clarksville, TN; Sese Industrial Services is adding a new plant to their operations in Chattanooga, TN to make axle components for the Volkswagen EV line; and in the Carolinas, Arrival is building a headquarters and two microfactories to produce electric delivery vans.

The increase in EV production, in response to growing sales, requires charging infrastructure to match consumer demand. In addition to the upfront cost, range anxiety remains one of the top reasons people and businesses are hesitant about switching to EVs. Federal efforts, like the Department of Transportation’s intention to build charging infrastructure throughout the National Highway System provide a solid start to the transition away from fossil fuels towards a more efficient, and cleaner transportation future.

The American Jobs Plan breaks with precedent not only by not encouraging any expansion of the existing road network, but alternately proposing more modern and affordable public transit and rail, road safety measures for pedestrians, and reconnecting neighborhoods historically harmed by highway projects. A more reliable and resilient energy infrastructure that supports electrification also will decrease emissions in communities disproportionately impacted by transportation pollution while also reducing our sensitivity to market volatility, offers new opportunities in utility services, and provides storage capacity for renewable energy that can keep people safe in the face of disaster.

The powerful combination of consumer demand alongside federal policy focused on electric transportation has the potential to transform our communities into healthy places to live and work, gives us more efficient ways to connect with one another and in more ways, and lays a foundation for healthier communities for all residents in the Southeast and nationally.

Going beyond recovery with the American Jobs Plan

For patients recovering from a major illness or trauma, doctors stress the importance of improving social wellness as a part of recovery. They prescribe getting back on your feet as the first step, but note that staying healthy requires a long-term investment in one’s physical, mental, and social health. In the American Job Plan, the Biden administration expands the definition of infrastructure beyond roads and bridges to include basic services, public institutions, and community resources. These shared assets bring people together, enabling them to meet their own needs and provide support to others. The plan marks a sea-change in public policy-making, explicitly calling for investments that support better physical, mental, and social health across our society. This reflects a fundamental shift in our cultural understanding of infrastructure and makes the case for social wellness as a prescriptive path to move America beyond recovery and back on its feet.

In 2009, the Obama administration responded to the Great Recession with the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act (Recovery Act). From 2009 to 2015, SEEA served as an Energy Efficiency and Conservation Block Grant (EECBG) administrator for the Recovery Act, coordinating 16 municipal governments and more than $20 million in grant funds across the Southeast. These local partners deployed a variety of programs providing public education and outreach, residential and commercial audits and retrofits, and a range of financing mechanisms for energy efficiency. In stewarding this cohort, SEEA witnessed the transformative effect that national infrastructure initiatives can have on the Southeast. The experience also gave us insight into how and why these efforts can fall short of addressing the most pervasive and systemic problems.

In economic terms the Recovery Act was a success. It reversed the financial crisis, created tens of thousands of jobs, and rescued the U.S. economy from a second Great Depression. The Southeast saw a 387% ROI on DOE’s $20 million investment in energy efficiency alone. Despite these gains, the impact of the Recovery Act was ultimately stunted by a civic and social infrastructure that was unable to fully leverage the funding due to decades of under-investment. The gush of capital overwhelmed understaffed state energy agencies, makeshift city sustainability offices, and weatherization services operating on shoestring budgets and volunteer labor. In many ways, the Recovery Act revealed the limitations of the Southeast’s ability to marshal resources, make plans, and tackle complex problems. This strategic vulnerability in public management capacity was further illustrated by the COVID pandemic.

The Recovery Act relied on large block grants and a competitive proposal process that left states and local government to figure out where and how to invest funds. While this supported innovation and experimentation, it also missed an opportunity to make long-term infrastructure investments and institute reforms to housing policy, health services, and other foundational areas. Failing to close these gaps meant that low-income communities and communities of color remained largely unable to fully participate in the Recovery Act or realize its benefits, let alone overcome systemic inequities in economic opportunity. In contrast, The American Jobs Plan expressly recognizes the nexus between social wellness and economic growth and makes addressing existing inequities a core component in infrastructure planning.

The American Jobs Plan is an ambitious, wide-ranging proposal that aims to modernize and electrify our vehicles and transportation system, increase the resiliency and clean energy capacity of the electrical grid, and rebuild and refurbish our homes and buildings to be more affordable, safe and healthy. The plan stimulates job growth and invests in a workforce to rebuild the middle class. If fully implemented, the American Jobs Plan would be the most transformational re-making of the American economy since the New Deal. The plan though, is just that, a plan. It faces a number of political and logistical hurdles. Obstacles aside, the framework itself is already transformative in presenting a more inclusive, more humanistic definition of infrastructure and what is needed for people to not only survive but thrive. It has changed the conversation, trajectory, and scope of infrastructure planning from this point forward.

The American Jobs Plan goes beyond the optics of shovel-ready, quick wins and reinforces the cornerstones of our physical, civic, and social infrastructure. The plan would accelerate the growth of clean energy and transportation technology sectors already driving employment across the Southeast. It recognizes housing and buildings as equally critical assets where meaningful investment can yield economy-wide benefits. Most significantly, the American Jobs Plan acknowledges the intersectional nature of poverty and would expand access to needed services such as healthcare, aging in place, childcare, education, and job training. Investments in these life enriching resources expands access to the jobs and benefits that come with revitalized roads, bridges, and energy systems.

The Recovery Act was a historic investment that got the Southeast energy efficiency field on its feet. The region is fortunate now to have more experience in designing and delivering energy efficiency programs, a better sense of what works, and a deeper bench of trained professionals ready to take the next leap forward. Now, with the American Jobs Plan’s emphasis on rural communities, and prioritization of equity and restorative justice, the Southeast has the opportunity to go beyond recovery and invest in a social wellness that sustains the regions trajectory toward a cleaner, more prosperous, and more equitable future.