Month: June 2021

All the places we’ll go – clean cars, trucks, buses, and jobs!

Anne Blair

America loves to drive. There are nearly 280 million vehicles on the road and the average person drives around 13,500 miles a year. The demand for transportation accounts for $1.9 trillion, or 9.1% of the GDP. We spend more money on transportation than we do on education ($1.4 trillion [6.5%]) and nearly as much as we do on food ($2 trillion [9.4%]). Our car-loving culture and transit-driven economy comes at a price beyond what we spend on vehicles and the gas that powers them. Our current system’s focus on personal, internal-combustion engine vehicles for every American was fueled by the creation of the interstate highway system in the 1950s and ‘60s. That sweeping infrastructure investment came at the expense of downtown, majority Black communities, and reliable mass transit systems in most American cities. Currently, just 3% of the trips Americans take are by mass transit.

Transportation is also the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the United States. Those emissions contribute to a warmer climate, higher rates of heat-related and respiratory illness, more severe weather, and sea level rise among other things. These factors increase the cost of healthcare, insurance, and housing. In the Southeast, the impacts of climate change are more disproportionately felt in low-income and Black communities. These neighborhoods are often bordered by transit corridors and lag in green infrastructure compared to wealthier or white counterparts.

Even accounting for emissions created by generating electricity, plug-in electric vehicles (EVs) are still three times cleaner than comparable gasoline-powered vehicles. However, there are only 1.8 million EVs currently registered in the U.S., representing less than 2% of all vehicles on the road. The U.S. market share of EVs is a fraction of the Chinese market and China has eight times as many charging points for EVs than America. With strategic investment, the U.S. has an opportunity to lead in EV manufacturing, infrastructure, drive down the price of EVs, increase demand, and create jobs.

The American Jobs Plan proposes expanding availability and access to energy efficient transportation by investing in a strong domestic supply chain for EVs and parts, growing the market for EVs, building a national network of charging infrastructure, creating an equitable and modern public transit system, and reconnecting communities that were purposefully divided by highway projects.

In the Southeast, EVs are revitalizing existing manufacturing infrastructure by adapting operations, or inviting new business. Blue Bird is making electric school buses in Fort Valley, GA; SK Innovation is building two battery facilities and just announced a joint venture with Ford Motor; Mercedes-Benz announced its Tuscaloosa County plant will start producing electric SUVs in 2022; Schnellecke Logistics Alabama is adding a new warehouse and jobs to support Mercedes-Benz; in Spring Hill, TN, GM is transitioning its existing plant to build electric vehicles and recently announced Ultium Cells LLC, a joint battery cell venture with LG Energy Solution; battery maker Microvast is building a new factory in Clarksville, TN; Sese Industrial Services is adding a new plant to their operations in Chattanooga, TN to make axle components for the Volkswagen EV line; and in the Carolinas, Arrival is building a headquarters and two microfactories to produce electric delivery vans.

The increase in EV production, in response to growing sales, requires charging infrastructure to match consumer demand. In addition to the upfront cost, range anxiety remains one of the top reasons people and businesses are hesitant about switching to EVs. Federal efforts, like the Department of Transportation’s intention to build charging infrastructure throughout the National Highway System provide a solid start to the transition away from fossil fuels towards a more efficient, and cleaner transportation future.

The American Jobs Plan breaks with precedent not only by not encouraging any expansion of the existing road network, but alternately proposing more modern and affordable public transit and rail, road safety measures for pedestrians, and reconnecting neighborhoods historically harmed by highway projects. A more reliable and resilient energy infrastructure that supports electrification also will decrease emissions in communities disproportionately impacted by transportation pollution while also reducing our sensitivity to market volatility, offers new opportunities in utility services, and provides storage capacity for renewable energy that can keep people safe in the face of disaster.

The powerful combination of consumer demand alongside federal policy focused on electric transportation has the potential to transform our communities into healthy places to live and work, gives us more efficient ways to connect with one another and in more ways, and lays a foundation for healthier communities for all residents in the Southeast and nationally.

Pursuing more equity in energy efficiency programs in the Southeast

SEEA’s approach to realizing a more efficient Southeast has grown in depth and reach in the eight years I’ve been with the organization. Our work increasingly spans a broad range of topics that are tied together by the aspiration for all people in the Southeast live and work in healthy and resilient buildings, utilize clean and affordable transportation, and thrive in a robust and equitable economy.

In May, we wrote about the game-changing potential of the American Jobs Plan. In addition to recasting the way we think about community, the plan includes a strong focus on providing opportunity for all Americans and to make amends for historic inequities built into the infrastructure of our country.

Last week, I had the pleasure of sharing how SEEA is thinking about its own contributions to a more equitable Southeast at the NEUAC 2021 Annual Conference. Our journey started at the tail end of our role in administering $25 million in funding from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act in 2013 but I’m going to fast forward to last year.

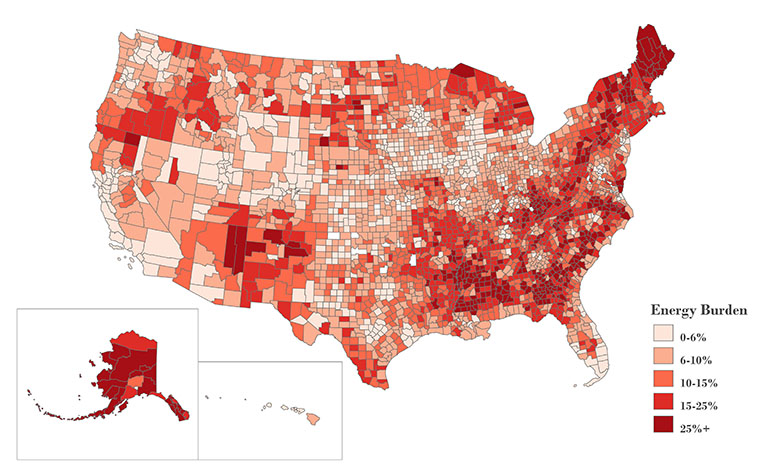

Like many organizations, SEEA felt an urgency to accelerate and deepen its work on racial justice and energy equity issues in the summer of 2020. In partnership with TEPRI, SEEA published Energy Insecurity in the South which illustrates the deeply rooted connection between historic racial and economic inequities and the region’s current struggle with energy burden, and Energy Insecurity Fundamentals for the Southeast, which further defines the multiple dimensions of energy insecurity, including energy burden.

Energy insecurity is pervasive, particularly in the Southeast. More than a third of the region’s population has trouble paying their energy bills. The Southeast has the lowest electric rates in the contiguous United States, but the highest residential bills.

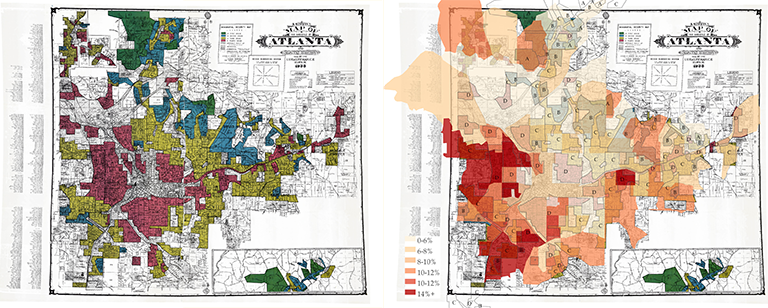

Housing segregation, or redlining, which led to disinvestment in communities of color, still shapes access to affordable energy in the South. Neighborhoods that were historically segregated often experience high levels of energy burden today.

So how does this relate to energy efficiency? At SEEA, we’re exploring how energy efficiency can relieve energy insecurity and provide other benefits such as improved health outcomes through better indoor environmental quality. The next step is to determine how to get energy efficiency to those who need it most.

I have sat in hundreds of hours of meetings collaborating with utilities and regulators to develop energy efficiency programs that serve the utility’s customers. In that time, I have witnessed utilities and regulators express more interest in improving energy efficiency programs for low-income customers and growth in program size and sophistication.

Through our work, we have learned that focusing on “low-income” is often a proxy for addressing equity. As SEEA confronted the reality of racial injustice, we learned about the history as well as the breadth and variety of challenges experienced by communities that have faced systemic discrimination. In Atlanta, the median energy cost burden is 32% higher for Black households and 52% higher for Hispanic households compared to white households.

Simultaneously, we learned about how to think about equity. Our understanding will continue to evolve, but for now we use the following dimensions of equity:

Procedural equity, or that all affected communities have a voice in the decision-making process;

Distributional equity, or that programs are designed to equally distribute its benefits and burdens to the entire community; and

Intergenerational equity, or programs that consider how future generations will be impacted by the decisions being made today.

We then began to think about where equity starts in the energy efficiency program development process. We focused on regulated investor-owned utilities (IOUs) because of their more mature and consistent approach. Program development begins with evaluating energy efficiency potential and setting a spending or savings target. After analysis and design, the programs are deployed, evaluated, and the cycle repeats. Many utilities periodically conduct energy efficiency potential studies to determine how much cost-effective energy efficiency is available in their service territory and for which customer classes.

In the first stage of energy efficiency program development, analyzing factors including, but not limited to, customer segmentation, housing type, language spoken in the home, and ethnicity shed light on the program’s equity. This analysis evaluates how different customers perceive and participate in energy efficiency programs, or its distributional equity. For example, rebate-based programs often exclude customers who either cannot afford upgrades or are renters who do not have control over upgrades to their homes.

We can address distributional equity through procedural equity. If representatives from the communities being served have the opportunity for their voices to be heard during program development, the program has a higher chance of reaching more customers in those communities. Finally, as the Energy Insecurity in the South StoryMap illustrates, are decision makers accounting for structural and transgenerational inequities?

During a virtual SEEA member meeting we held last year to discuss long-term innovations in energy efficiency programs, we heard emphatically that, “energy efficiency needs more teachers!” Meaning, when programs and the people that deliver those programs don’t listen to the experiences and circumstances of the people they serve, those programs will reach fewer customers. When programs are delivered by contractors who are trained to listen to the needs of the customer, establish trust, and guide them through the process, programs are much more sustainable and successful.

Lastly, what indicators do we use to measure success, and how does equity factor into that evaluation? SEEA is currently developing a data collection and stakeholder engagement plan that will shape a guide to help decision makers at commissions and utilities consider equity throughout the energy efficiency program development process and develop approaches that meet their particular needs.

Energy efficiency is an evolving set of solutions that expands alongside our individual and organizational capacity for empathy. The Southeast has the greatest opportunity for growth in energy efficiency and an opportunity to ensure that prosperity reaches everyone.

We’ll continue to keep our members informed as we make progress in this area, in the meantime, please contact Cyrus Bhedwar, director of energy efficiency policy, with any questions or feedback.