July Map of the Month

By Grace Parker

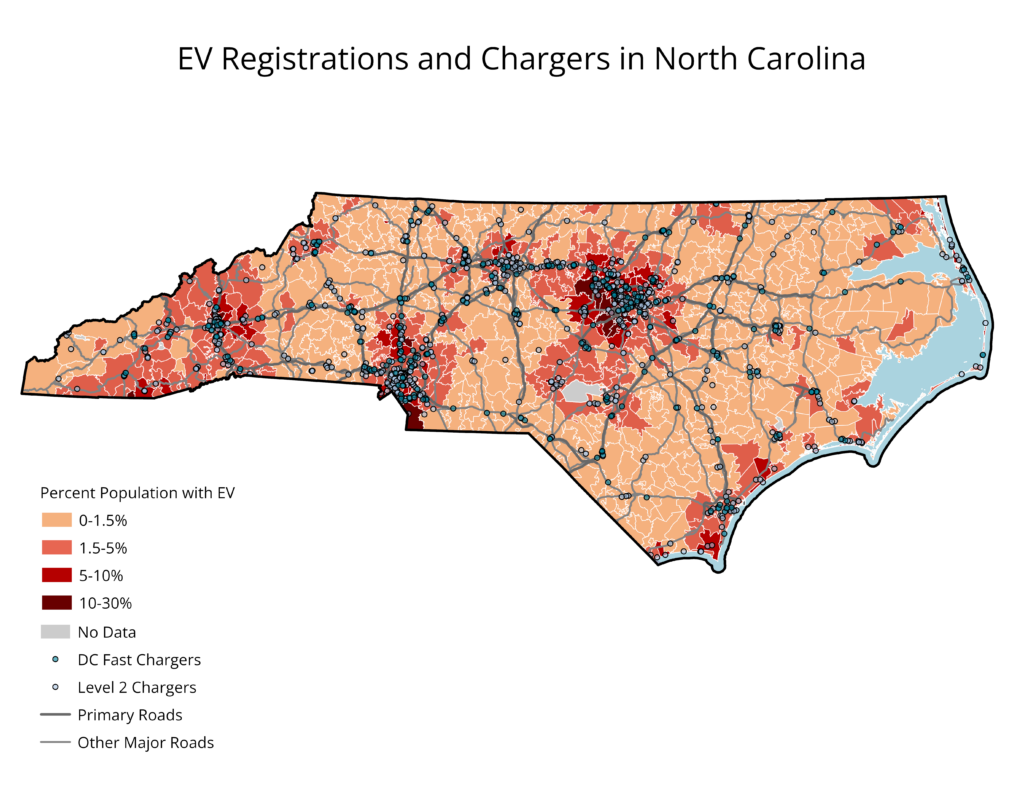

Source: Alternative Fuels Data Center and EV Hub

Historically, the development of transportation infrastructure in the United States has exacerbated inequities by displacing people of color and contributing to residential segregation. Without thoughtful approaches, the build-out of electric vehicle (EV) infrastructure has the potential to contribute to inequities through access and affordability disparities. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) provides funding to build 500,000 public EV chargers by 2030. Where these chargers are sited will play a key role in determining who can drive an EV and where air pollution is reduced.

In 2021, a MIT study reported that EV buyers were “mostly male, high-income, highly educated, homeowners, who have multiple vehicles in their household, and have access to charging at home.” The barriers to greater EV adoption are multidimensional, but expanded public charging access can make EVs a compelling option, particularly for renters and residents in multifamily housing who are unable to install charging equipment. Many stakeholders have a role in siting public EV chargers, including local governments, state transportation agencies, utilities, and private property owners, and all can play a role in making EV chargers more accessible.

Using data from the Alternative Fuels Data Center and Atlas Public Policy’s EV Hub, this month’s map shows that EV registrations are highly correlated with the number of public EV chargers. The roughly 1,650 public level 2 and fast charging stations in North Carolina and the areas of greatest EV adoption are both centered in the state’s most population-dense areas, including the Research Triangle, Charlotte, and the Piedmont Triad.

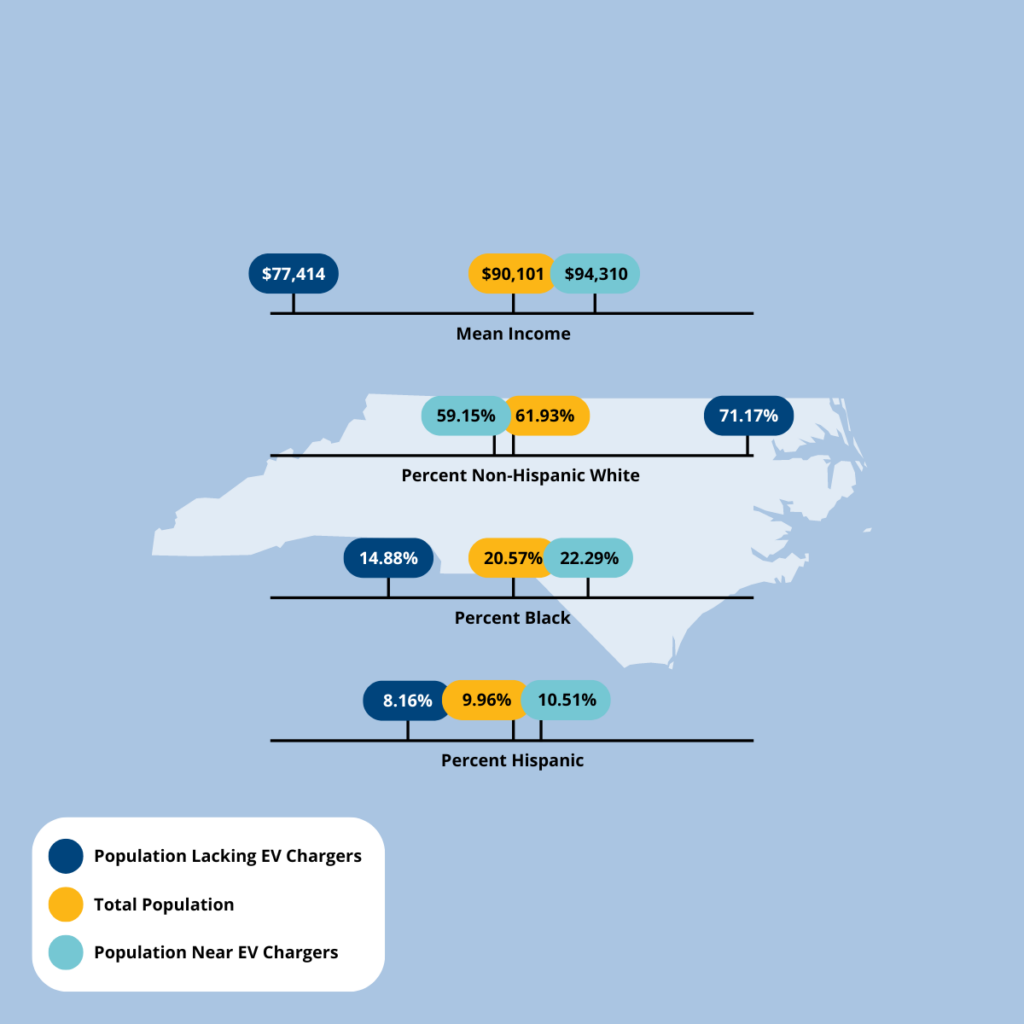

About 23% of the state’s population lives in a charging desert, which we define here as more than five miles from the nearest public charger. We found that this population had a significantly lower mean income of about $77,400 than the population overall at $90,100. While it is well-documented in other areas that people of color have less access to public chargers, at this scale we found that the population with charging access had higher proportions of Black and non-white Hispanic residents than the general population and those without charging access. This might be due to the urban-rural differences in racial composition, prioritization of equity in EV charger siting, or simply the geographic scale at which we did this analysis.

Many barriers to EV charging access cannot be captured by location, including the need for a smartphone or a subscription and associated costs such as expensive garages. Even where public charging is common, it can be 2-4 times more expensive than at-home charging, making it comparable to fuel costs for vehicles with internal combustion engines, and cutting into the fuel savings that make EVs a competitive purchase.

It’s crucial that, while building out public infrastructure, policies also prioritize at-home charging and EV purchase incentives. A variety of approaches have been implemented nationally to extend EV adoption to lower-income and multifamily building residents. Beginning January 1, 2024, the federal $7,500 tax credit was made available at the point of sale, extending it to lower-income households with less tax liability. Some states and utilities have set aside rebates specifically for multifamily property owners or low-income households. These policies help ensure that funding is directed to those for whom it is most impactful.